DAVID HARTT: Et in Arcadia Ego

-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by David Hartt entitled Et in Arcadia Ego. The show at the gallery runs concurrently with the artist’s project at The Glass House in New Canaan, CT. David Hartt’s first collaboration with the historic site took place last year and provided the setting for the new film the artist produced for his exhibition at David Nolan Gallery.

Hartt’s film Et in Arcadia Ego, commissioned by The Glass House, responds to Philip Johnson’s mid-century modern residence and the surrounding landscape. Opening with roving camera shots of the various sites within the grounds— the house, the garden and the pavilion—the presence of Johnson and his partner, David Whitney, is immediately felt. The architect’s legacy is multifaceted, undeniably cemented into the canon of modern architecture, and complicated by his history with fascism. Hartt builds his narrative on top of this structure, both aware of and despite its layered, complex history. By centering bodies outside of the dominant narrative, through the lens of Black authorship, a uniquely compelling alternative is forged.

The ‘Arcadia’ of Hartt’s imagination is idyllic and teeming with life, yet solitary, inhabited only by Olimpia, played by the composer Tomeka Reid, who wrote the score for the film. She is watched over by Orion, the blind giant, recast as a Black woman in glimmering chainmail. So named for their mythic origins, the characters inhabit archetypes of stories past. The ubiquity of folklore suggests its constant capacity for change and elevation because the core of these fables are enduring metaphors.

We imagine Olimpia’s days are as typical as the one we happen upon, she wakes up, writes and records music. In the living room, she contemplates the Burial of Phocion, Nicolas Poussin’s depiction of the funerary procession of the condemned Stoic soldier, sequined chain-mail fluttering in the breeze. Though it appears she lives in utopia, the painting functions as a memento mori. Her helmet, cast with pristine metallic finish, recalls the costuming of Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, the highly influential avant-garde performance originated at the Bauhaus. The aesthetic sensibilities of the Bauhaus profoundly influenced Johnson; he also collected Schlemmer’s work and later donated it to the Museum of Modern Art.

Olimpia attracts the giant with her music, and there is a sense that both come in peace. Lighting a highway flare, she restores Orion’s sight. The film’s final image is rich with symbolism: the flare, synonymous in this political and cultural moment with civil unrest and the continued fight for liberation serves as a guiding, revitalizing light. Hartt synthesizes and weaves together the historical context and creative potential of the pastoral grounds with Greek legends to produce contemporary mythology.

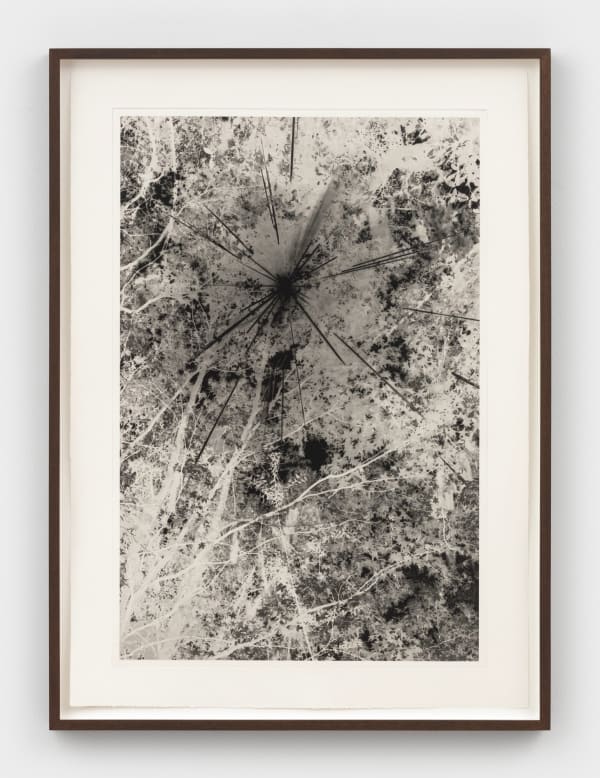

The film is accompanied by a poster, tapestry, sculpture, and platinum print. The tapestry, A Colored Garden, references the artist’s first project at the Glass House of the same name. In his research, Hartt encountered the work of Charles Ethan Porter, a Black still-life painter of the post-Civil War era, who resided primarily in Connecticut.

Porter was the first African American student at the National Academy of Design in New York, which afforded him the attention and patronage of Mark Twain and Frederic Church. Though still-life painting had fallen out of favor as Impressionism grew in influence and popularity, Porter remained committed to rendering flora local to his surrounding Connecticut. For the garden, Hartt composed an array of plant life frequently found in Porter’s paintings. His photograph of the peonies in bloom is reproduced as a Jacquard-woven tapestry, alluding to the tradition Porter was ceaselessly indebted to as well as the art-historical tradition of textiles.

The platinum print shows Olimpia in repose, clad in sequined chainmail regalia and mirrored helmet. Her presence is simultaneously relaxed, imposing and meditative, a contemporary and distinct contribution to the art of portrait-making. A bronze casting of Olimpia’s helmet sits in the space; the sleek surface reflects and distorts one’s own image as you gaze into it. The perfect object is evocative of Constantin Brancusi’s seductive sculptures, which were aspirational, ideal forms. Printed on the poster is the phrase ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’, which translates to ‘Even in Arcadia there am I’. The text is stylized to mimic the ‘I am a man’ posters used during the Memphis Sanitation Workers strikes in 1968, when Black workers refused to work, calling for safer working conditions, union recognition and fair wages. Asserting one’s own dignity and rightful personhood speaks to a perpetual struggle for representation and agency. The phrase encapsulates Hartt’s ethos; he does not seek to obscure, negate or rewrite history, rather to renegotiate its boundaries to invent and permit new pathways and realities.

David Hartt (b. 1967, Montréal, Canada) has been included in many solo and group exhibitions, currently at The Glass House in New Canaan, CT, and previously at The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Beth Sholom Synagogue, a Frank Lloyd Wright designed landmark in Philadelphia, as well as shows at The Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, CO. Hartt’s work is included in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; RISD Museum, Providence, RI; and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, among others.

David Hartt: Et in Arcadia Ego is commissioned by The Glass House, a site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. A concurrent project, A Colored Garden, is on view at The Glass House from April 22 to November 14, 2022. The projects are supported in part by the Canada Council for the Arts and the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Marge and Joe Grills Fund for Historic Gardens and Landscapes. For more information and advance ticketing, visit theglasshouse.org.

-

Installation Views

-

-

Artist