To our modernist sensibility, one of the hallmarks of (Neo)Classicism is inscription, or the placing of words – usually commemorative, often epigrammatic – upon objects in a carefully chosen setting. Inscription, even when hidden or only implied, is the device that animates and, importantly, provocatively "arms" almost all of Ian Hamilton Finlay's art, and it has derived naturally from Finlay's very earliest work as a concrete poet. To "inscribe" words or other signage (signs being, in Finlay's hands, but abbreviations of language) upon a sheet of paper, a stone plinth, a fine ceramic vase, a patch of landscape is at once to give these words or signs a physical, or stubbornly phenomenological, as well as formal dimension and to wildly complicate their connotative, or "semiotic," roles. At a single blow, through "neoclassical" inscription, Finlay enables language to occupy – now aggressively, now plaintively – the real world, to engage visual art's formal concerns, and to undergo a shift, usually a radical and revitalizing transformation, in its meanings.

Finlay's now famous garden, Little Sparta, set in the windswept hills of Southern Scotland, is itself a protracted poetic inscription upon a once barren upland; and it borrows its forms and intention from the 18th -Century Neoclassical tradition of the garden as a place, in Finlay's own words, "not (of) retreat" but of "attack" – a place eliciting serious or "noble" poetic, philosophic and even political thought. The remarkable inscription that is Little Sparta, in an action recapitulated by each of the works exhibited here, moves through the concrete and literal in order to vividly recapture the Ideal. "For grove," Finlay has admonished, read "Grove"; for woods or streams, read "Woods" and "Streams"; for vase, read "Vessel." Finlay's works not only sensuously – irresistibly – inhabit their material or natural settings; they also forcefully invoke an intangible – a metaphorical – landscape stretching "in space" as far as the distant Sea and "in time" as far as Classicism's Golden Age. For Finlay, the Sea (or virgin Nature), the Golden Age with its living gods, the Rousseau-ian Wildflower, the mighty weaponry of modern warfare are all images of purity, uncompromised power and perfect transparency or immediacy of expression. Yet inscriptions, as Finlay's still empty vases and abraded stone tablets ineluctably recall, are commemorative and thus inherently elegiac. They, together with the words and the very concepts they would (re)embody, remain but flawed substitutes – frail and belated signs – for a withdrawn perfection, the vanished Ideal. The gods of antiquity have decamped; the sea is tamed and landlocked; the absent wildflower is only a memory in the mind's eye; the weapons have been put to base uses; and, critically, art like the garden flower has become merely decorative, its practice an irrelevant formalist exercise.

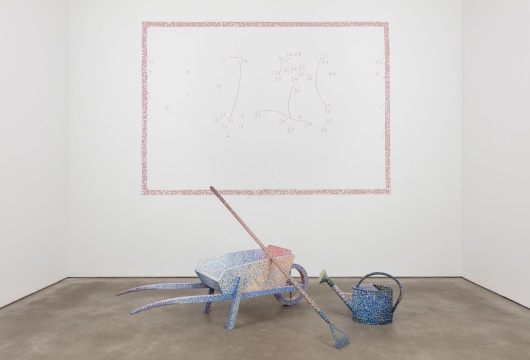

Finlay's enterprise is the fierce countering of this loss and debasement. His inscriptions, while elegiac, never convey a sense of dusty anachronism. Instead, they freshly assail and quiz us. A Finlay work hinges, for its evocative power, upon an always striking and unsettling divergence – a seeming incongruence – between inscribed word(s) and setting, between "text" and "context." This divergence serves to undercut the literal meaning, or given identity, of both the words (or signs) and their setting: each term radically redefines the other, transforming it into a full-blown metaphor. The transformation – metamorphosis – from literal to figurative is redemptive because profoundly redefining; and, in the strongest of Finlay's works, the new metaphorical meaning that is sparked can be audaciously both urgent and open-ended. The gods are brought back to us – if figuratively, then also newly created, updated, revitalized and re-armed. Abetting this "re-armament program" is Finlay's elliptical use of language, his extreme economy of means. A Finlay inscription, at once laconic – often riddling-ly so – and magnificently allusive, is intended to waylay the viewer. And it is finally we, through the very act of a keenly imaginative interpreting or "reading," who are led to re-quicken again the Ideal.

Prudence Carlson