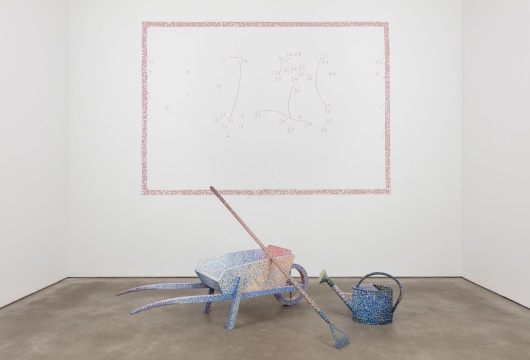

Ian Hamilton Finlay

Homage to Seurat, 1995

wall painting, painted wheelbarrow, painted hoe, painted watering can, with Gary Hincks and Candida Ballantyne

wall painting: dimensions variable

wheelbarrow: 18 1/8 x 52 x 22 1/8 in (46 x 132 x 56 cm)

hoe: 61 3/8 x 4 7/8 x 1 5/8 in (156 x 12.5 x 4 cm)

watering can: 15 3/4 x 24 3/8 x 8 7/8 in (40 x 62 x 22.5 cm)

Ian Hamilton Finlay

ROUSSEAU (Sour Vase) / A Wild Flower is Ideological, Like a Badge, 1991-93

cast bronze, and ceramic vase (vase with David Ballantyne)

cast bronze: 27 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 11 in (69.8 x 26.7 x 27.9 cm)

ceramic vase: 5 1/2 x 3 3/8 in (13.9 x 8.5 cm)

Ian Hamilton Finlay

Urn 1794, 1993

stone

21 1/4 x 10 5/8 x 10 5/8 in

54 x 27 x 27 cm

Ian Hamilton Finlay

Fire Earth Water Air, 1979

three ceramic tree plaques, with David Ballantyne

each: 9 1/8 x 13 x 2 in (23 x 33 x 5 cm)

Ian Hamilton Finlay

Only Connect, 1998

stone

7 7/8 x 11 1/2 x 1 7/8 in

20 x 29.2 x 4.7 cm

Ian Hamilton Finlay

EVENING, 1967

unique wall painting

dimensions variable

Ian Hamilton Finlay

“The garden became my study”

September 13 – October 27, 2018

Opening reception: Thursday, September 13, 6 - 8pm

David Nolan Gallery is pleased to present “The garden became my study”, an exhibition of work by conceptual artist Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006). On view from September 13 through October 27, the exhibition brings together works associated with the artist’s most celebrated achievement – Little Sparta, a classical garden that he built on a farm in Stonypath near Edinburgh. Created over four decades, Little Sparta fuses many of Finlay’s artistic concerns, from the French revolution, to the classical world, and nature. The display will include works incorporating sculpture in bronze, wood, ceramic, and stone, as well as three text-based wall paintings. This is the artist’s tenth exhibition at the gallery, and has been organized in collaboration with Pia Simig and the Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay.

Finlay’s fascination with past eras is succinctly encapsulated by his dictum: “It is quite a natural process to use other times to understand your own time”. In particular, the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau were a continued source of inspiration to the artist. A key figure of the Enlightenment, Rousseau’s philosophy embodied late 18th-century Romanticism and influenced the development of the French Revolution. Finlay viewed Rousseau as a prototypical philosopher of the natural world, a perception that influenced a number of his key works.

L'Idylle des Cerises (2005) is a two-part stone sculpture conceived in the final years of Finlay’s life, and centers on Rousseau’s posthumously published autobiography, Confessions. Envisioned for a garden, Finlay’s installation is inspired by a passage from the fourth volume of Confessions, known as the “The Cherry Idyll” – a light hearted account of Rousseau's evening stroll through a cherry orchard with two girls. The excerpt, inscribed on the stone wall relief, details Rousseau’s recollection of his climb up a cherry tree, throwing cherries down to the onlookers. The freestanding carved stone sculpture memorializes Rousseau’s account, inviting the viewer to experience in person a basket of cherries.

Finlay’s bronze bust, ROUSSEAU (Sour Vase) (1991) – cast from an original by Jean-Antoine Houdon – resided for many years in the entry hall of Little Sparta. The text inscribed on the base is an anagram of Rousseau’s name, “Sour Vase”. On a shelf below the bust is a vase bearing the text “A Wild Flower is Ideological, like a Badge”. Rousseau was an avid botanist, which he alludes to in his writing, famously indicating his preference for “wildflowers and grasses as opposed to the inkstand or the writing desk”.

Other works in the exhibition make reference to nature and the garden by way of art historical allusions. Homage to Seurat (1995) is part of a group of artworks that playfully honor modern artists and movements (others include Homage to Malevich and Homage to Pop Art). In this installation, Finlay references Georges Seurat’s series of paintings of the harbor at Port-en-Bessin. Using the format of a wall painting, Finlay converts the composition into a series of dots and numbers that – as in a child’s game of “connect the dots” – can be traced in sequential order to reveal the hidden imagery. In the foreground are presented items from a garden – a wheelbarrow and a watering can – which Finlay wryly “camouflages” in hundreds of tiny dots evoking Seurat’s pointillist technique.

For Finlay, the garden was not simply a place of beauty, but rather a liminal space bordered by nature and culture, where visitors are invited to meditate on the different ways time passes.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Marcel Broodthaers and Cy Twombly: I see them sitting in a neoclassical gazebo overlooking a shimmering lake, talking passionately about poetry, different kinds of script (from handwriting to calligraphic lettering to typefaces), gardens, and the distinction between cultivated flowers and wildflowers. Their literal writing — from Finlay’s concrete poems to the pairing of words and images in Broodthaers’s graphic works to Twombly’s transcriptions of poems by various poets — is what initially enthralled me, but this early enchantment has blossomed into much more. Like many poets of my generation, I first learned about Finlay when I came across his concrete poems in the indispensable gathering, An Anthology of Concrete Poetry, edited by Emmet Williams, and published by the legendary Something Else Press, under the guidance of Dick Higgins, in 1967. Recalling that early encounter — I was in my first year of college — I wonder if it was Finlay’s playful variations on the same letters and words that interested me in the possibility of language being something to both to read and look at? Or did the roots of my fascination start much earlier, when I was a child happily watching my mother using a brush and ink to practice her calligraphy on Sunday afternoons?