JIM NUTT: Shouldn't We Be More Careful?

-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is delighted to announce Shouldn't We Be More Careful?, a solo exhibition of recent drawings by Jim Nutt, marking the first time in more than a decade that the artist has shown in New York. Titled after a 1977 Nutt painting, Shouldn’t We Be More Careful? will feature works on paper created in 2022 and 2023, and organized in close collaboration with the artist. The exhibition will be on view from September 6 through October 14, 2023.

Although Nutt’s name remains indelibly linked with “Hairy Who,” the group of Chicago artists exhibiting in the late 1960s and early 70s known for their perverse, surreal and humorous psychosexual aesthetic, his work over the past four decades has had an almost singular focus: representations of a single imaginary figure. While Nutt’s earlier works on paper often functioned as preparatory sketches for his luminous, portrait-like paintings, his recent drawings stand as complete works in their own right, a quietly virtuosic display of the artist’s exquisite and perfect control of line and form.

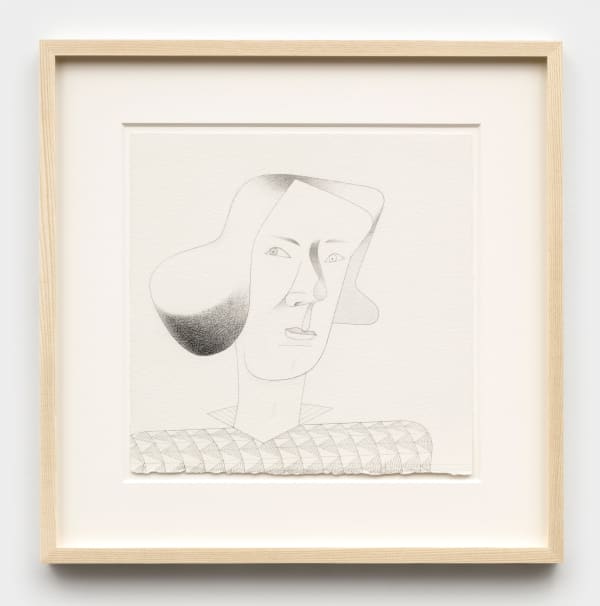

Nutt draws in graphite on cold pressed paper, its toothy surface utterly unlike the smooth plexiglass on which he painted his earliest works. The paper’s rough texture is visible even in Nutt’s thin and exacting lines, some so light and delicate that one starts to wonder whether they are actually present or simply a trick of the eye. Erasure marks are apparent, too; tactile evidence that the artist remains as fastidious a draftsperson as ever, committed to the iterative process required to achieve his own standard of perfection.

For Nutt, each drawing begins as a formal problem, a question of line or gesture rather than any preconceived narrative or meaning. Within an intimate scale, he demonstrates a dazzling array of solutions: an eyebrow can be conveyed in an emphatic dash, a closed arc, a procession of dancing squiggles; noses are architectural constructions of undulating lines and open loops cantilevered on pointed teardrops; lips are plumped with just three hard lines.

Each individual feature, it seems, is space for Nutt to lavish attention, and none more so than his subjects’ hair, whimsically sculptural spaces that he furnishes with meticulous cross hatching, tonal gradations and sinuous patterning. As Nutt always portrays his figures from shoulder height, their upper garments frequently provide another repository for his decorative work. With a few exceptions, Nutt’s newest works display the greatest economy of line — a masterful efficiency of gesture that can render a mass of hair in one extravagant loop, an elegant collarbone in a single ruler-straight line, a regal poise in the expressive curve of a shoulder or neck.

Nutt has stated that he has always considered his subjects female, yet they increasingly possess an androgynous beauty, with strong features and steady gazes that suggest a rich interior life. That mysterious interiority, however, may remain as unknownable to the artist as to the viewer: Nutt’s figures are entirely the inventions of his own mind, which is to say, the collective impressions of a lifetime of attentive looking. In earlier conversations, he has compared his process to that of a writer, starting with the suggestion of a personality and evolving it into something more specific through the act of mark making.

Nutt refrains not only from giving the drawings titles, but also from speculating on their meaning, in an effort to resist some fixed interpretation. And while his reticence may frustrate some critics and interviewers, Nutt’s refusal to situate his work within any particular narrative offers the viewer more room to connect with a perspective different than her own. Just as the imaginary characters in a novel compel us to experience their emotional vicissitudes alongside them, so, too, does Nutt invite us to a place that is beyond mere surface appearance and into the mystery of being human, with all its searching, tender, quirky, weird and beautiful possibilities.

Jim Nutt (b. 1938, Pittsfield, MA), gained recognition in the late 1960s as a member of the exhibiting group of Chicago artists known as the “Hairy Who” (later regarded under the broader umbrella of Chicago Imagists), along with his wife, Gladys Nilsson, and four other recent graduates of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. At a moment when the art world was dominated by New York Abstraction, Nutt presented a provocative alternative that depicted lurid, malformed figures engaged in acts of violence, sexual perversion and scatological humor with exacting precision. While the work unwittingly succeeded in challenging the reigning visual aesthetic, Nutt has insisted that the exhibits were simply “an enthusiastic response of wanting to make something.”

Informed as much by comic books and pinball machines as by folk art and Northern Renaissance portraiture, Nutt has developed a singular style over his distinguished career while influencing countless artists as diverse as Jeff Koons, Mike Kelley, and Carroll Dunham. His numerous solo exhibitions include the Milwaukee Art Museum, WI; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL; and San Francisco Art Institute, CA. Recent group exhibitions include the Smithsonian American Museum of Art, Washington, D.C.; Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London; Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI; Tang Museum, New York; Met Breuer, New York; Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Austria; Morgan Library & Museum, New York; RISD Museum, Providence, RI; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Fondazione Prada, Milan; and Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, HI; among others.

Nutt’s work is included in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL; Ball State Museum of Art, IN; Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, MA; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C.; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; amongst others. Nutt lives and works in Chicago.

-

Installation Views

-

-

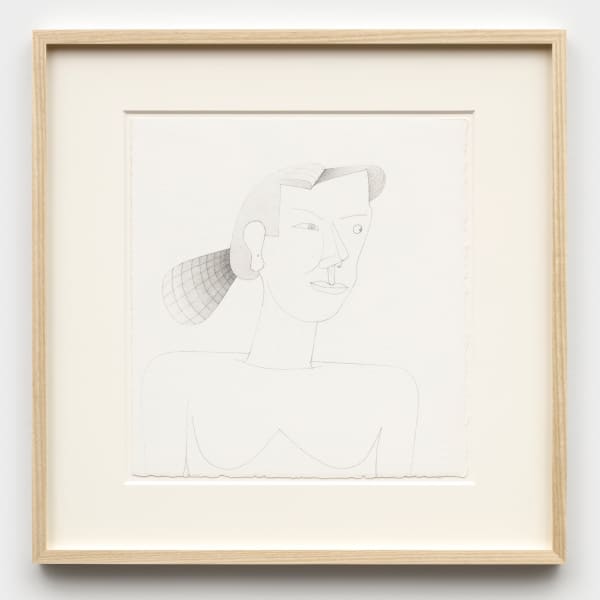

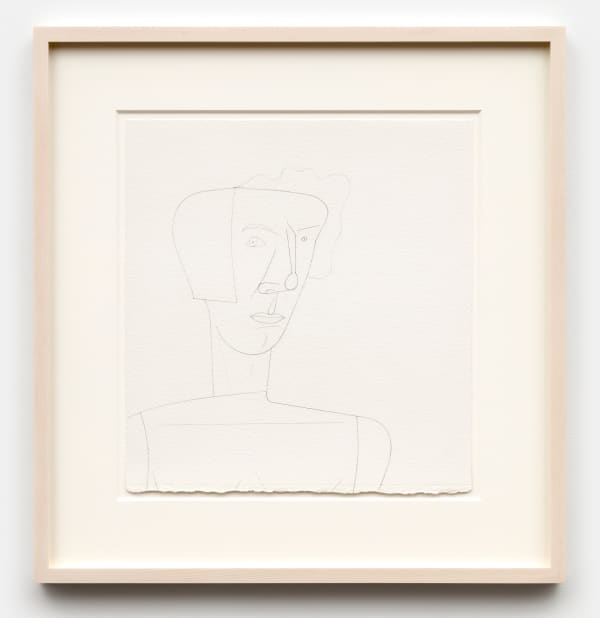

Jim NuttUntitled, 2023graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2023graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

framed: 22 3/8 x 22 3/8 in (56.8 x 56.8 cm) -

-

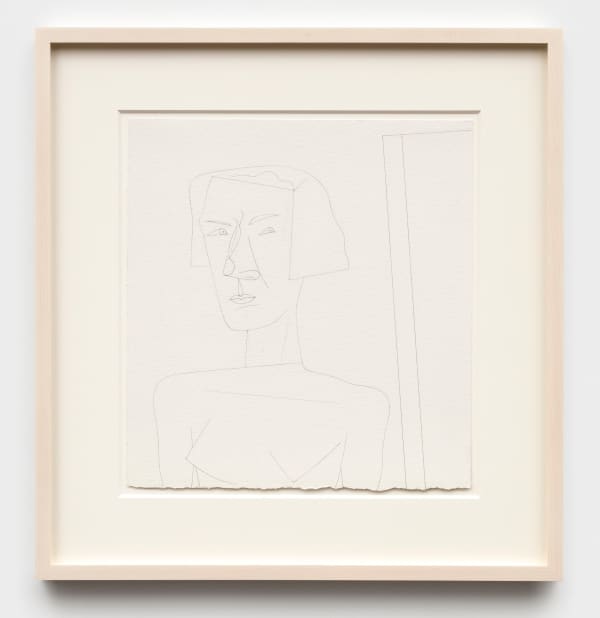

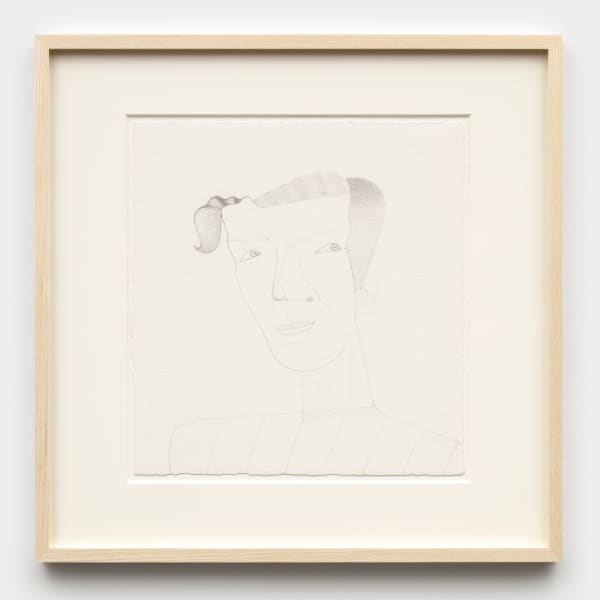

Jim NuttUntitled, 2023graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2023graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

framed: 22 3/8 x 22 3/8 in (56.8 x 56.8 cm) -

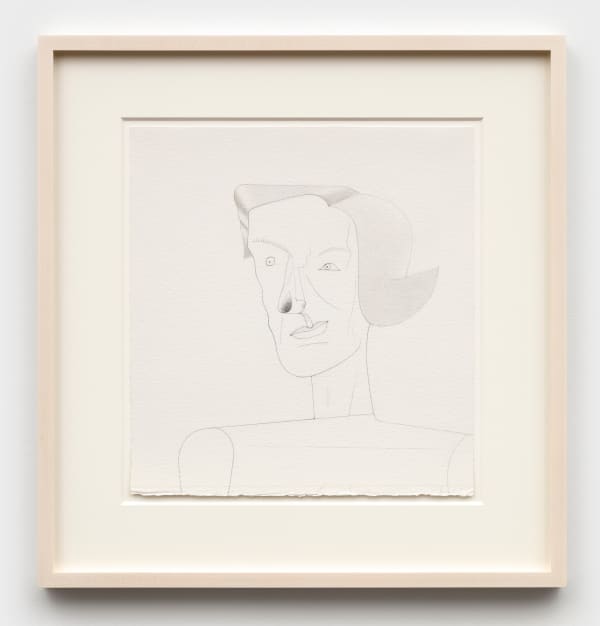

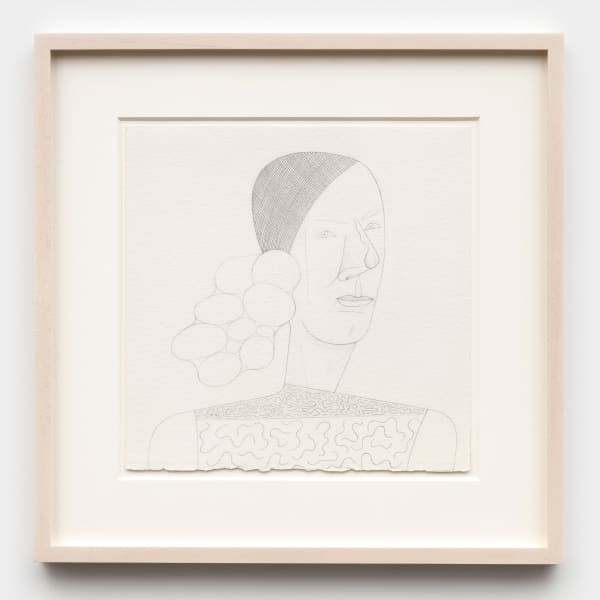

Jim NuttUntitled, 2023graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2023graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

framed: 22 3/8 x 22 3/8 in (56.8 x 56.8 cm) -

-

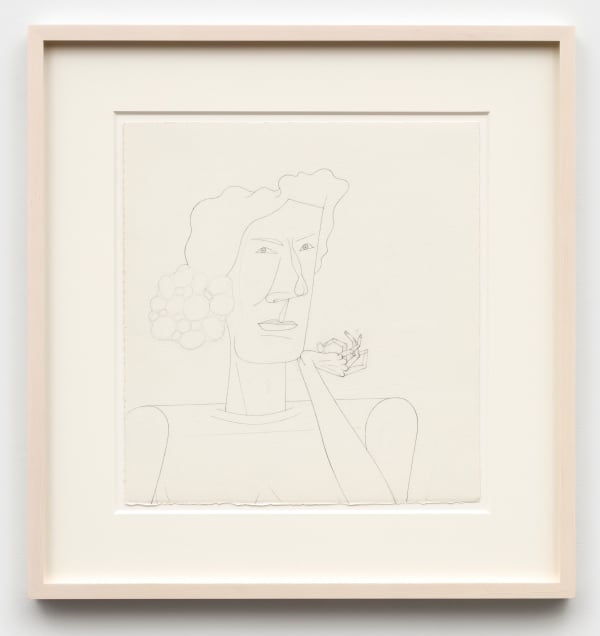

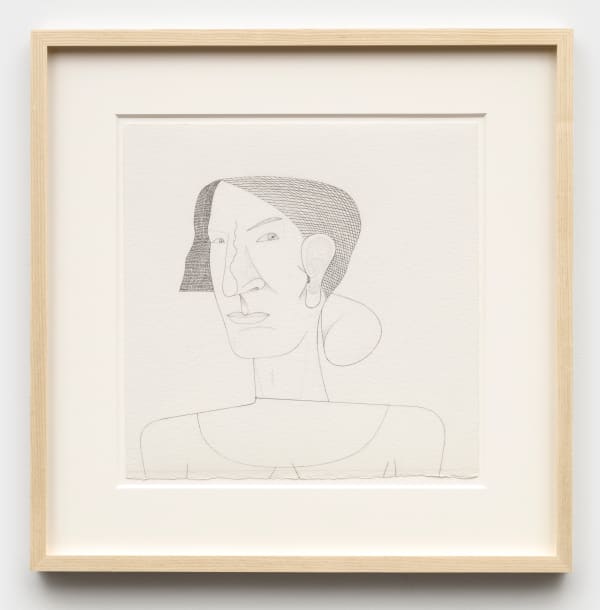

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

framed: 22 3/8 x 22 3/8 in (56.8 x 56.8 cm) -

-

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper15 x 14 in (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

framed: 22 3/8 x 22 3/8 in (56.8 x 56.8 cm) -

-

-

-

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper13 x 13 in (33 x 33 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper13 x 13 in (33 x 33 cm)

framed: 20 x 20 in (50.8 x 50.8 cm) -

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper13 x 13 in (33 x 33 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper13 x 13 in (33 x 33 cm)

framed: 20 x 20 in (50.8 x 50.8 cm) -

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper13 x 13 in (33 x 33 cm)

Jim NuttUntitled, 2022graphite on paper13 x 13 in (33 x 33 cm)

framed: 20 x 20 in (50.8 x 50.8 cm) -

-

-

PRESS

-

Jim Nutt: Shouldn’t We Be More Careful?

Patricia Lewy · Brooklyn Rail October 4, 2023Jim Nutt: Shouldn’t We Be More Careful, currently at David Nolan Gallery, offers an all-too-rare exposure to the acerbic and piquant portrait drawings of this contemporary master. In Nutt’s recent... -

Jim Nutt’s Art Deserves a Closer Look

John Yau · Hyperallergic September 21, 2023Jim Nutt’s painting and drawing go totally against the grain of internationally celebrated postwar American art. His independence and the fiercely self-reliant artistic ambition that has fueled his work have... -

Jim Nutt’s Art Remains a Mystery. Even to Him.

Max Lakin · The New York Times September 13, 2023In his first show of new work in over a decade, he has been occupied with a single subject: a portrait of a woman, in which he finds endless variation... -

The Critic’s Notebook

The Editors · The New Criterion September 6, 2023“Jim Nutt: Shouldn’t We Be More Careful?” at David Nolan Gallery, New York (September 6 through October 14): Jim Nutt may have been one of the founders of the “Hairy... -

Jim Nutt

Barry Schwabsky · Artforum September 1, 2023For wealthy tourists in early-nineteenth-century Rome, it was de rigueur to visit Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres to have one’s portrait drawn. Such works were mere bread and butter for an artist who...

-

-

Artist