Julia Fish

First plan for floor [ floret ] — section one, 1998

gouache on assembled, laser-printed paper

23 1/4 x 23 1/4 in (59.1 x 59.1 cm)

(JF6293)

Julia Fish

First plan for floor [ floret ] — section two, 1998

gouache on assembled, laser-printed paper

11 3/4 x 23 1/4 in (29.8 x 59.1 cm)

(JF6294)

Julia Fish

First plan for floor [ floret ] — section four, 1998

gouache on assembled, laser-printed paper

12 x 23 1/2 in (30.5 x 59.7 cm)

(JF6296)

Julia Fish

First plan for floor [ floret ] — section three and six, 1998

gouache on assembled, laser-printed paper, diptych

left: 23 1/4 x 16 1/2 in (59.1 x 41.9 cm)

right sheet: 23 3/4 x 17 3/4 in (60.3 x 45.1 cm)

(JF6307)

Julia Fish

Study for floor [ floret ] # 5, 1998

hand-stamped ink on laser-printed vellum

22 x 86 1/2 in (55.9 x 219.7 cm)

(JF4608)

Julia Fish

floret

Gallery 2

January 11 – February 18, 2017

Special event with the artist, in conversation with curator Kate Nesin: Thursday, January 26, 6.30pm

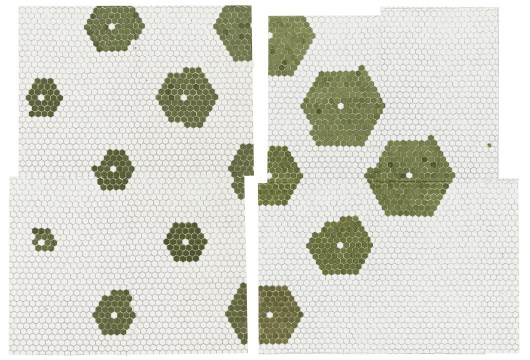

David Nolan Gallery is pleased to present Julia Fish: floret, an exhibition of five works on paper that were conceived in conjunction with her site-specific installation: floor [ floret ], at Ten in One Gallery in 1998. Shown now for the first time – 18 years after the original installation – the varied studies serve not only as documents to the project but also offer a glimpse into the artist’s formative working process.

Located near the intersection of North Damen and Milwaukee Avenues, Ten in One Gallery occupied a street-level storefront space in the Wicker Park neighborhood of Chicago. Within the gallery, the hexagonal-tiled floor with stylized “floret” patterning – commonly found in commercial spaces – served as the foundation for Fish’s installation. Planned in exacting detail on an expanse of assembled laser-printed sheets, the artist devised a numerical algorithm in which individual florets would enlarge and contract, indicating multiple paths through the space. Using a green gouache to designate the colored accumulations, the now discreet sections from the original layout appear unexpectedly abstract and belie their intricate and intentional workings.

In making the physical installation, Fish worked with custom-color, die-cut vinyl material to systematically and precisely cover the white tiles immediately surrounding the existing green floret designs, with the effect of progressively enlarging the clusters from three directions towards the center of the main gallery. Describing her experience in the space, critic Kathryn Hixson wrote at the time:

“The gallery was completely ‘empty’ of any expected works of art, so there was no getting away from Fish’s floor-bound intervention… As I walked through the gallery, the ebb and flow of tiles beneath my feet swelled to almost complete blackness.” If the human experience became the animating factor of Fish’s installation, the accompanying works on paper invite comparisons to nature: like flowers in a garden through different seasons of the year, the green floret takes time to reach viral bloom.

Kate Nesin is associate curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. Her book Cy Twombly's Things was published by Yale University Press in 2014, and she holds a doctorate in art history from Princeton University. At the Art Institute Nesin has curated solo exhibitions of work by Lucy McKenzie, Frances Stark, and Kemang Wa Lehulere, among others.

On view concurrently in our main gallery is Barry Le Va: Cleaved Wall.

At the time of the project installation, the artist offered these acknowledgements for support and expertise:

Joel Leib, Director, Ten in One Gallery; University of Illinois /UIC, partial funding;

Tom Van Eynde, photography; Jason Pickleman /JNL Graphic Design;

LAB ONE, Chicago; RED STAR printing : die-cutting;

Avantika Bawa, Shona Macdonald, Helen Mirra, Sue Scott : installation assistance.

I don’t think it is quite right to say that Julia Fish is the Emily Dickinson of abstraction, but I don’t think it is completely wrong either. For many years now, Fish has been making work based on the incidental details of her house, garden, and studio; while her paintings and drawings may treat a commonplace feature— a square or hexagonal tile — its repetition in her compositions becomes expansive.

As we know, the reclusive Dickinson did not leave her house for the last twenty years of her life, but she was a keen observer and, in her poems, she was able to seamlessly meld abstract concepts with concrete images, envisioning the extraordinary out of the ordinary in familiar terms:

I’ll tell you how the Sun rose

– A ribbon at a time