MEL KENDRICK: Cutting Corners

-

Overview

What first drew me to Mel Kendrick’s work more than 20 years ago was the total immediacy of his sculptures in the round: playful, fresh and full of vitality. I found them incredibly smart, both rough and sophisticated in all the right ways. I thought of Constantin Brancusi rather than Naum Gabo; rather than an inscrutable intellectualism, the works possessed a powerful physicality. – David Nolan

David Nolan Gallery is delighted to announce an exhibition of new works by Mel Kendrick titled Cutting Corners, the artist’s first solo exhibition since his celebrated 2021 traveling museum retrospective. The show will include wood sculptures created within the past twelve months, along with works on paper. Mel Kendrick: Cutting Corners, Kendrick’s eighth solo exhibition with the gallery, will be on view from March 7 through April 13, 2024.

Over the course of five decades, Kendrick has established himself as a preeminent American sculptor, pushing the boundaries of the medium through a rigorous and sustained commitment to discerning a work through the process of making it. Though often mentioned in relation to artists such as Sol LeWitt for his conceptual underpinnings, Dorothea Rockburne for her mathematically driven processes, Eva Hesse for her expansive use of materials, and Martin Puryear for his minimalist treatment of wood, Kendrick remains a singular figure in his open and experimental approach to what he has called “drawing within a material.” The famed 2009 installation of five monumental black and white conctrete sculptures in Madison Square Park, New York, demonstrated Kendrick’s prowess as a public art sculptor.

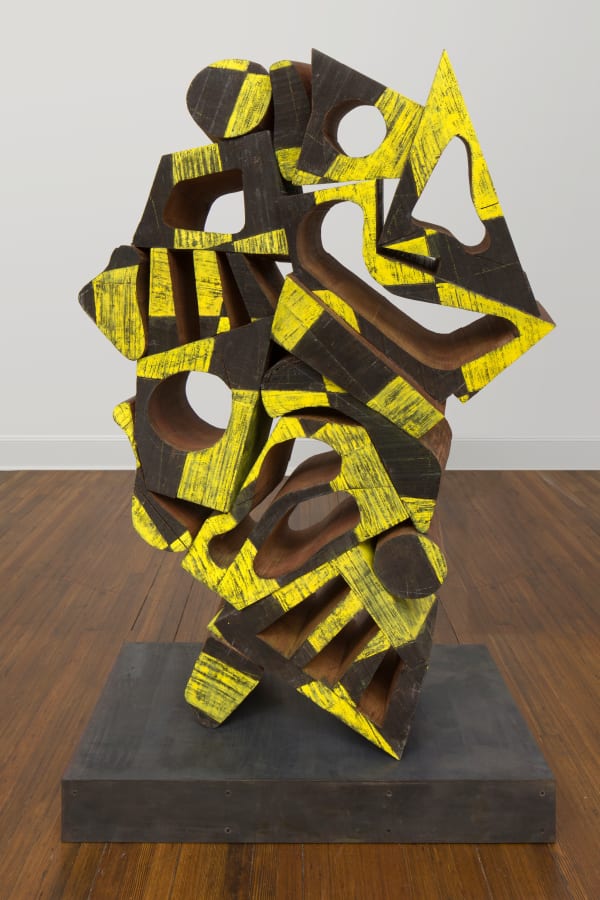

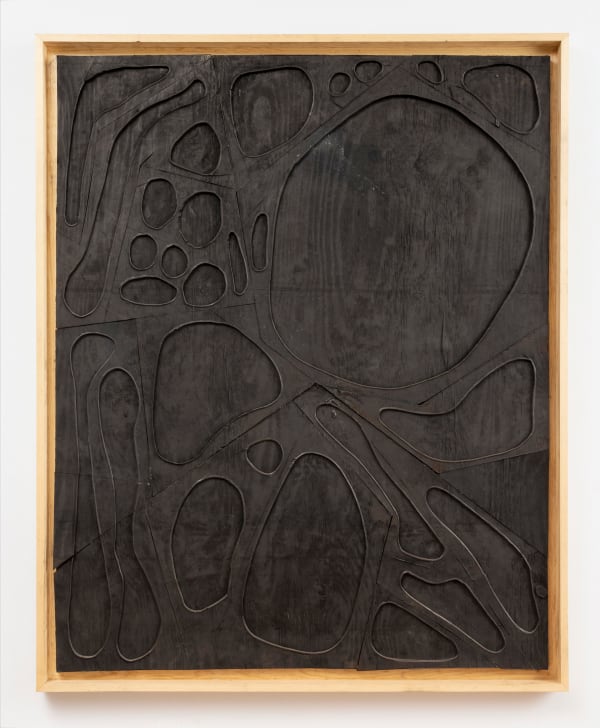

With a material ingenuity and formal inventiveness, Kendrick transforms single blocks of wood into optical puzzles, carving parts from the whole only to reassemble them atop or alongside the excavated base. In this elegant economy of both form and material, nothing is ever wasted, nor is anything added; each block is a question that contains its own answer. The result is something akin to a visual fugue: independent geometric systems are built up within a single composition to create a complex and dazzling harmonic whole, celebrating and complicating their own material and conceptual logic.

Self-contained and self-referential, Kendrick’s works bear the evidence of their own making and, crucially, the struggles, errors and mistakes inherent in that process. Graphite marks, paint drips, saw cuts, and fingerprints are all layers of information, markers along a timeline, as if the sculptures were not so much finished pieces as they are stopping points at particular moments within the continuum of creation. And while the wood grain always remains visible, even under a layer of Japan paint, each step in Kendrick’s process of assembling, carving and reassembling the wood blocks seems to further remove the material from its ecological origins and push it toward a uniquely physical (rather than theoretical) abstraction.

Indeed, as Kendrick has continued to evolve and reinvent himself within his distinct visual language, his free-standing and pedestal-based works have acquired a new weightiness and thickness, with heavy wood, steel and concrete bases that connect them with the floor. The works have a mass and gravity, an earth-bound physicality, that’s countered by their dynamic movement and energy, with lyrical curves and rounded pieces repeated and stacked in undulating cascades. Bands of black, white and yellow Japan paint pull the viewer from section to section, weaving in and out of negative space, from the ostensible front to what could be its reverse, in an elaborately playful game. As the viewer attempts to mentally reassemble the sculpture’s constituent parts, the artist confounds our ideas of perception and materiality.

-

Installation Views

-

-

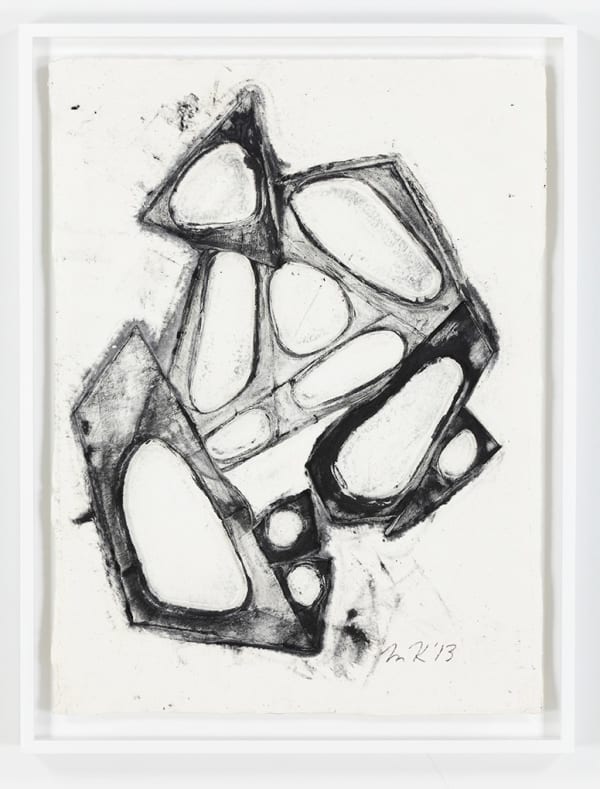

Mel KendrickCell (G), 2013cast paper and carbon black pigment30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

Mel KendrickCell (G), 2013cast paper and carbon black pigment30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

framed: 33 3/4 x 25 3/4 x 1 3/4 in (85.7 x 65.4 x 4.4 cm) -

-

-

Mel KendrickUntitled, 2024mahogany and gesso20 x 12 x 14 in (50.8 x 30.5 x 35.6 cm)

Mel KendrickUntitled, 2024mahogany and gesso20 x 12 x 14 in (50.8 x 30.5 x 35.6 cm) -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Mel KendrickUntitled, 2024mahogany with gesso and charcoal31 x 14 1/2 x 9 in (78.7 x 36.8 x 22.9 cm)

Mel KendrickUntitled, 2024mahogany with gesso and charcoal31 x 14 1/2 x 9 in (78.7 x 36.8 x 22.9 cm)

-

-

Press

-

Mel Kendrick: Cutting Corners

Barbara A. MacAdam · Brooklyn Rail April 23, 2024In this rich, dense, and compact show, Mel Kendrick focuses on his generally solid, large, puzzle-like sculptures, most in his current signature tones of yellow and black, creating a dynamic... -

Mel Kendrick: Cutting Corners

Elena Clavarino · Air Mail April 18, 2024“Every sculpture is only a point in time,” the American artist Mel Kendrick has said. “Every object could go further.” Kendrick, born in 1949, has dedicated his life to sculpture,... -

Our Mid-March Picks of New York City Art Shows

John Yau · Hyperallergic March 18, 2024Mel Kendrick: Cutting Corners Mel Kendrick doesn’t like to waste anything. When he cuts a cylindrical form out of a thick block of wood, what he removes becomes part of... -

Four Upper East Side Powerhouse Galleries to Visit This Spring

Annabel Keenan · Avenue March 11, 2024A staple of the New York art scene since 1987, David Nolan Gallery established itself with locations in SoHo and Chelsea before making the Upper East Side its home in...

-

-

Artist