-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is pleased to present the exhibition Radical Artists of the 1960s/1970s: Between Geometry and Gesture, featuring works by Barry Le Va, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Dorothea Rockburne, and stanley brouwn. The exhibition will be on view September 5 through October 26, 2024 at the gallery’s Upper East Side location, half a block from the Met.

When one considers the political unrest, economic uncertainty, racial tension, and even the anti-war demonstrations at New York’s major art institutions, the uneasy atmosphere of the late 1960s in the United States doesn’t feel that far from our current moment. An energetic consumerism was fueling the Pop Art movement, while other artists were challenging both the postwar supremacy of Abstract Expressionism and the strict formalism of Minimalism. Following Marcel Duchamp’s philosophy of complete artistic freedom, movements like Performance Art and Fluxus were pushing art into new material and conceptual experimentation, while the concurrent Arte Povera movement in Italy was espousing the use of inexpensive materials, such as dirt and rags. It was from this heady confusion of cultural rebellion and social upheaval that a handful of artists were radically reshaping the boundaries of artmaking and shattering all preconceived notions of what art could be.

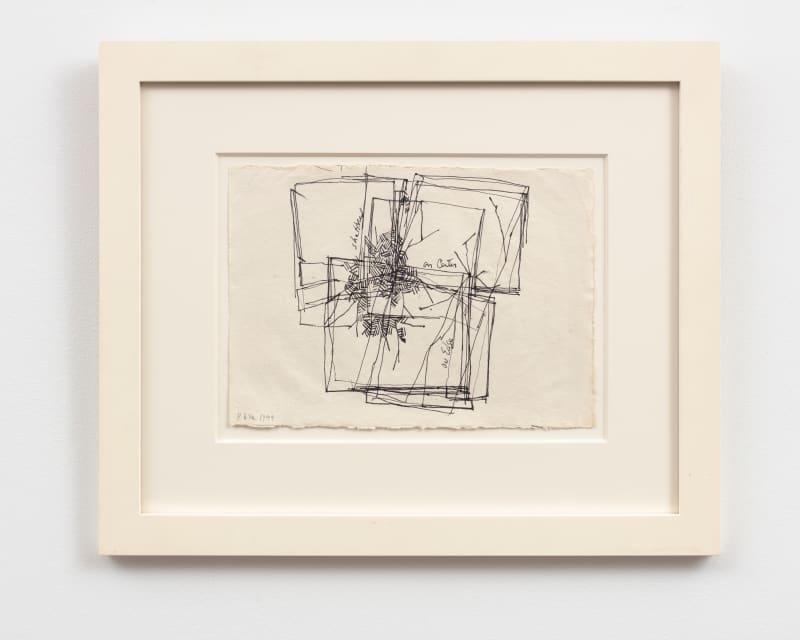

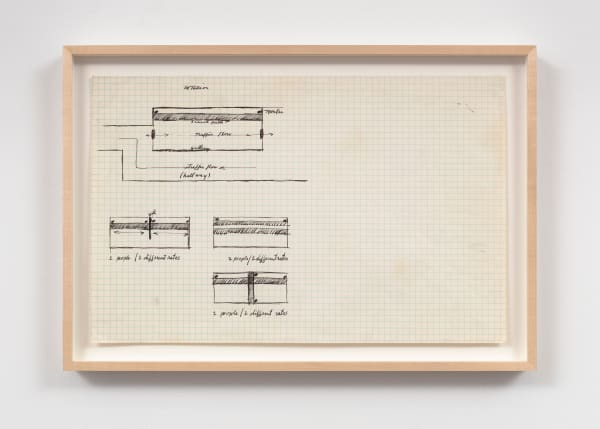

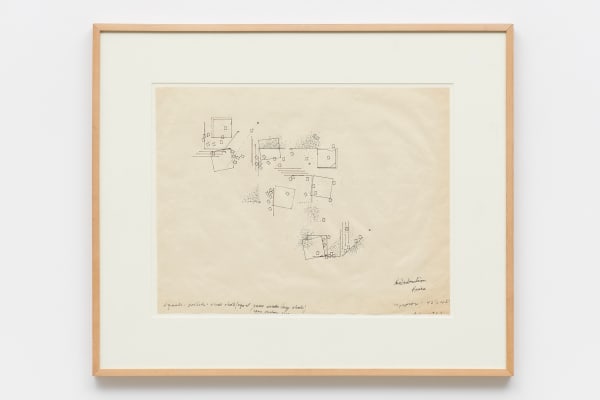

As one of the leading figures of what would come to be known as Process Art, Barry Le Va upended the conceit that sculpture had to be fixed, contained or even beautiful. More interested in the actions of artmaking than the end result, Le Va claimed the entire gallery space as his arena with the enactment of his first Distribution Pieces in 1966, dispersing commonplace materials like felt, glass and ball bearings across the floor in a series of improvised gestures within the gallery’s fixed geometry. (The current exhibition includes drawings related to the installation’s various permutations that reveal the chaos to have been, in fact, meticulously planned.) In doing so, La Va not only expanded the concept of sculpture, but also opened it up to a new physicality, bringing the viewer into relationship with the artwork, and the work in relation to the architecture that surrounded it.

Rather than looking at a single object, audiences were invited to walk around and immerse themselves in the work. Le Va, a fan of Sherlock Holmes, wanted to arouse in viewers a curiosity about the past actions that had created the present arrangement of materials. Titles often offered clues, such as a stack of shattered glass he called 4 Layers: Placed, Dropped, Thrown (1968-71). Perhaps unsurprising given the turmoil of the time, many of Le Va’s early works allude to an unseen violence, such as his signature meat cleaver pieces or Impact Run Velocity Piece (1969), an audio work in which he repeatedly ran across a gallery, hurling his body at its opposing walls for an entire hour. When the recording was later played in the empty gallery, audiences had only audio clues (and the surrounding architecture) to piece together what had transpired.

Elsewhere in Lower Manhattan, Richard Serra was compiling his own list of action verbs (“to splash, to spread, to bind, to weave”) and enacting them in relation to industrial materials like fiberglass, neon and rubber, more concerned with exploring their physical properties than in generating any specific result. Short films, such as Hand Catching Lead (1968), reflect a contained intensity of energy and focus, as well as a liberating disregard for conventional conceptions of sculpture and film. In a further affront to the art establishment, Serra flung molten lead at the juncture of a wall and a floor for his Splash Piece series (1968-70); when the lead cooled, he was left with a cast of his action: bodily gesture writ permanent and solid. Like Le Va, Serra drew incessantly throughout his career in a practice that both informed and was independent from his sculptures, and in the 1970s began using black paintstick on wall mounted linen to explore relationships between viewer and form through large repetitive gestures.

Similarly, Dorothea Rockburne viewed drawing as a material way of thinking, a process in its own right rather than a means to an end. Extensively influenced by both mathematics and dance (she studied with mathematician Max Dehn at Black Mountain College and later joined the Judson Dance Theater in New York), Rockburne’s works of the early 1970s suggest both an intellectual rigor and an emotional depth. In her series Drawing Which Makes Itself, Rockburne combined the gestures of dance with the elegant geometries of nature: folding, scoring and unfolding a white sheet of paper and, in the process, dismantling all definitions of what constituted a drawing. Once again, the viewer is left with faint clues to the artwork’s making, ghostly remnants of prior actions, and a drawing that is as much a sculpture as it is a flat piece of paper.

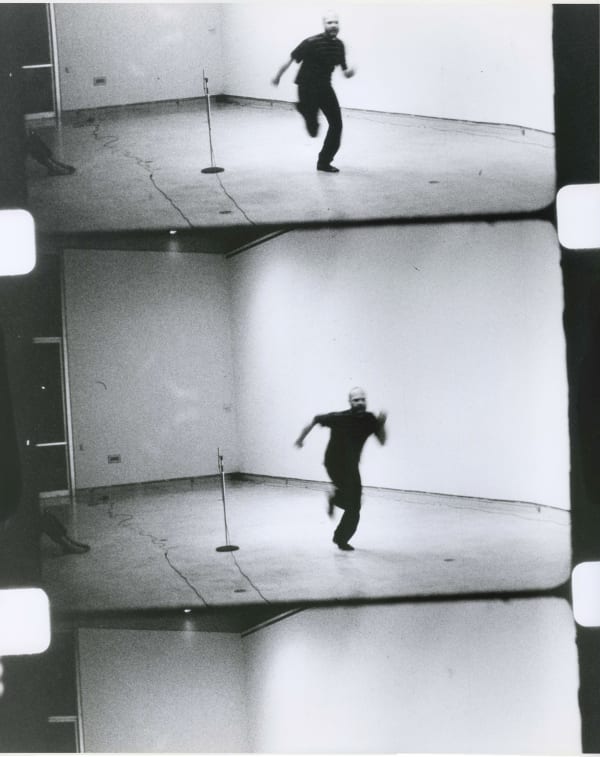

While his peers were carrying out investigations with everyday commercial and industrial materials, Bruce Nauman was documenting his explorations of what art could be on film, recording himself performing activities as simple as walking around his studio, using his entire body as a gesture and helping to inaugurate video art as a new medium. The idea of studio-as-canvas was one to which Nauman would return throughout his career, such as his 2001 work Sound for Mapping the Studio Model (The Video), an asynchronous presentation of ambient audio with surveillance like video footage of one evening in his studio. Though Nauman’s early works were recorded with 16-millimeter film, he quickly moved on to utilize the first consumer video cameras, again reflecting the Post-Minimalists’ embrace of cheap, readily available materials.

In radically expanding the use of materials, overturning disciplinary hierarchies, and challenging the very idea of what art could be, this group of pioneering artists had an outsized significance within a broader movement that irrevocably altered contemporary art, influencing countless artists as diverse as Jason Rhoades, Mike Kelley, Rachel Whiteread, Monica Bonvicini and Mel Kendrick. From a turbulent and often violent moment in American history, they succeeded in creating change that was profound, enduring and—despite their best intentions—beautiful.

-

Installation Views

-

-

-

-

Bruce NaumanStamping in the Studio, 196816 mm film transferred to video, black-and-white, sound62 min.

Bruce NaumanStamping in the Studio, 196816 mm film transferred to video, black-and-white, sound62 min. -

Bruce NaumanManipulating the T- Bar, 1965-196616 mm film transferred to video, black-and-white, sound6 min., 22 sec.

Bruce NaumanManipulating the T- Bar, 1965-196616 mm film transferred to video, black-and-white, sound6 min., 22 sec. -

-

Richard SerraHand Catching Lead, 196816mm black-and-white film, silent; 3:30 min.

Richard SerraHand Catching Lead, 196816mm black-and-white film, silent; 3:30 min. -

Richard SerraC.C. XI, 1983-84oilstick on paper42 1/2 x 54 in (108 x 137.2 cm)

Richard SerraC.C. XI, 1983-84oilstick on paper42 1/2 x 54 in (108 x 137.2 cm) -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Dorothea RockburneLocus, 1972Portfolio with complete set of 6 double-sided aquatint etchings with folding and embossing on Strathmore paper. Printed by Crown Point Press, San Francisco. Published by Parasol Press, Ltd., Portland.

Dorothea RockburneLocus, 1972Portfolio with complete set of 6 double-sided aquatint etchings with folding and embossing on Strathmore paper. Printed by Crown Point Press, San Francisco. Published by Parasol Press, Ltd., Portland.

With the original wooden box.each sheet, unfolded: 40 x 30 in (101.2 x 77.0 cm) full margins, loose and folded as issuedEdition of 42 -

-

-

-

-

Press

-

Radical Bodies, Radical Minds and the Challenge of Measuring Space at David Nolan Gallery

Elisa Carollo · Observer September 30, 2024The show currently on view explores the relation between the space and the body through the work of artists like Barry Le Va, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Dorothea Rockburne and... -

Here Are 11 Must-See Gallery Shows This Armory Art Week

Artnet News September 5, 2024The temperature outside is cooling, but in the galleries of New York City, it’s heating up with a crop of exciting and timely gallery shows. All across Manhattan, as visitors... -

The Must-See Gallery Shows Opening During Armory Week

Elisa Carollo · Observer September 3, 2024Amid the backdrop of the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement, social change and art became inextricably intertwined in a movement fueled by a handful of artists that will...

-

-

Artist

MAILING LIST SIGN-UP

By completing this form, you confirm that you would like to subscribe to DAVID NOLAN’s mailing list and receive information about exhibitions and upcoming events. Your email address will be used exclusively for the mailing list service.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.