-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is delighted to announce Richard Artschwager: Boxed In, an exhibition celebrating the centennial of the iconoclastic artist’s birth. On view from December 15, 2023 to January 20, 2024, the exhibition will include drawings, paintings and sculptures spanning six decades of Artschwager’s impressive and protean oeuvre.

Born on December 26, 1923, Artschwager was always amused by the fact that his birthday was known as Boxing Day in many countries — a fact that is itself amusing given the artist’s refusal to be boxed in as any particular type of artist. While often mentioned in relation to such diverse artists as Edouard Vuillard, Georges Seurat, Giorgio Morandi, Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, Donald Judd, and Bruce Nauman, Artschwager moved through different mediums, materials, and visual preoccupations with a voraciousness, intelligence and wit that allowed him to escape any box the art world might have wanted to construct around him.

And yet, Artschwager would return to boxes, squares and rectangles throughout his career, employing them as framing devices to emphasize an object’s physical presence, and in turn our own experience of viewing the work. Mirrors, too, brought the viewer into the work (literally) and extended the picture plane into the physical world. Even his blps — those iconic, lozenge-shaped voids he installed in public places with the illicit delight of a graffiti artist — were driven by a deep critical engagement with the process of looking. Though Artschwager’s stated ambition may have been to “be original,” one might argue that his ultimate aim was more humanistic: to get us to look closely at the world around us and, through seeing, to begin to know it.

Take, for instance, one of his early sculptures, Description of a Table (1964), and its subsequent variations: a plywood box covered in Formica, with a woodgrain pattern to resemble the legs and top of a table, and black and white laminates to convey a spatial void and a tablecloth, respectively. In creating a flat representation (in Formica) of a dimensional object (a table) on another dimensional object (a wooden cube), Artschwager challenges not only our optical perception, but also our cognitive understanding of what constitutes a table. This deliberate confusion of the pictorial and the sculptural, often infused with a sense of irony and irreverence, runs throughout his work — a desire both to entertain and to disrupt our experience of the world.

Artschwager was playfully subversive in his choice of materials as well, eschewing canvas, brass and bronze for the cheap commercial stuff of everyday American life: the aforementioned Formica with its faux woodgrain and marble veneers, the rough fibers of Celotex ceiling tile that disturbed the surface of his paintings, the rubberized horsehair he removed from its original context as an upholstery filling and made visible outside of its furniture. One suspects that, more than exalting these materials in particular, the artist is urging viewers to a greater regard for all things ordinary, a willingness to see everything as worthy of extended observation.

Artschwager was adept at destabilizing the audience’s perspective on a large scale, too, as when he exhibited a collection of handmade shipping crates, transforming the containers of artwork into the artwork itself. True to his capacity for endlessly investigating a single subject, he would go on to make 100 of these crates over the years, shaped as the imaginary sculpture or painting they could possibly house, before making miniature sets of them that became beloved domestic objects. (The Formica tables underwent a similar miniaturization, testament to his perpetual fascination with scale.)

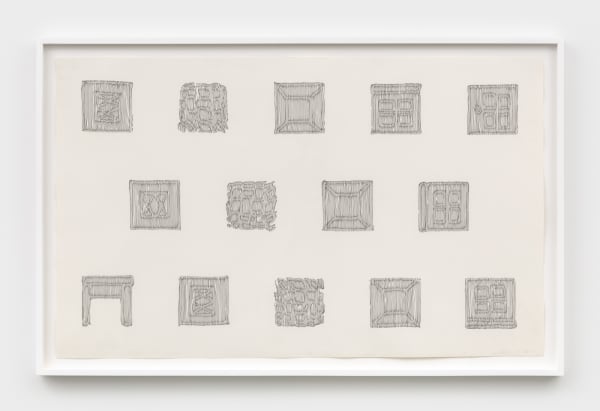

The more mundane the object, it seems, the more appealing it was as fodder for Artschwager’s fertile imagination, and none were more banal than the six — Door, Window, Table, Basket, Mirror, Rug — that together ignited a multi-decade obsession beginning in the 1970s. Through drawings, paintings, objects and multiples, he generated hundreds of permutations of these domestic objects, variously exaggerating perspective, surface and scale to often surreal and comic effect. Artschwager’s highest devotion, perhaps, was not to art but to the art of looking, and looking long enough to see the world as it is: strange, weird, funny, and wonderfully confounding.

Richard was rigorous and exacting in his own eccentric way. He was an artist, a scientist, and a philosopher with a Beckett-like sense of humor. Through his work, he demanded freedom of thought and spirit, and he was always looking for connections among objects, literature and the environment. He was absolutely brilliant, bursting with brains and wildly imaginative. That’s part of why so many artists across generations and around the world continue to admire him so much. - David Nolan

Richard Artschwager (b. 1923, Washington DC; d. 2013, Albany, NY) forged a unique path in art from the early 1950s through the early twenty-first century, making the visual comprehension of space and the everyday objects that occupy it strangely unfamiliar. After receiving a BA in 1948 from Cornell University, New York, he studied under Amédée Ozenfant, one of the pioneers of abstraction. In the early 1950s, Artschwager was involved in cabinetmaking before he began making sculpture using leftover industrial materials; he then expanded into painting, drawing, site-specific installation, and photo-based work. As an artist, he specialized in categorical confusion and worked to reveal the levels of deception involved in pictorial illusionism, striving to conflate the world of images — which can be apprehended but not physically grasped — and the world of objects, the same space that we ourselves occupy.

Artschwager has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions, first at the Art Directions Gallery, New York, NY, and then with Leo Castelli in 1965. Other solo exhibitions include Neues Museum, Nuremberg, Germany; Museum für Angewandte Kunst (MAK), Vienna, Austria; Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland; Museum of Contemporary Art, Miami, FL; Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin, Germany; Contemporary Art Museum, Saint Louis, MO; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York; among others.

-

Installation Views

-

-

-

Richard ArtschwagerTable (Drop Leaf), 2008Formica on wood30 x 22 x 44 in (76.2 x 55.9 x 111.8 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerTable (Drop Leaf), 2008Formica on wood30 x 22 x 44 in (76.2 x 55.9 x 111.8 cm) -

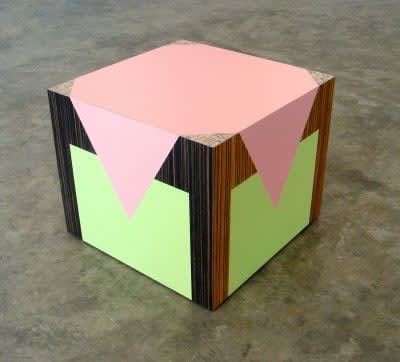

Richard ArtschwagerSmall Red Table, 2008wood and melamine laminate15 x 15 x 15 in (38.1 x 38.1 x 38.1 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerSmall Red Table, 2008wood and melamine laminate15 x 15 x 15 in (38.1 x 38.1 x 38.1 cm)

unique -

-

-

Richard ArtschwagerHair Box, 1969rubberized hair12 x 9 1/4 x 11 3/4 in (30.5 x 23.5 x 29.8 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerHair Box, 1969rubberized hair12 x 9 1/4 x 11 3/4 in (30.5 x 23.5 x 29.8 cm) -

-

-

Richard ArtschwagerZeno's Paradox, 2004suite of four etchings with color aquatint and drypoint, and a sculpture/portfolio of rubberize horsehaireach print: 19 1/2 x 23 1/4 in (49.5 x 59.1 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerZeno's Paradox, 2004suite of four etchings with color aquatint and drypoint, and a sculpture/portfolio of rubberize horsehaireach print: 19 1/2 x 23 1/4 in (49.5 x 59.1 cm)

sculpture: 25 1/4 x 22 1/8 x 5 in (64.1 x 56.2 x 12.7 cm)Edition of 25 with 20 AP's, published by Brooke Alexander, New York -

-

-

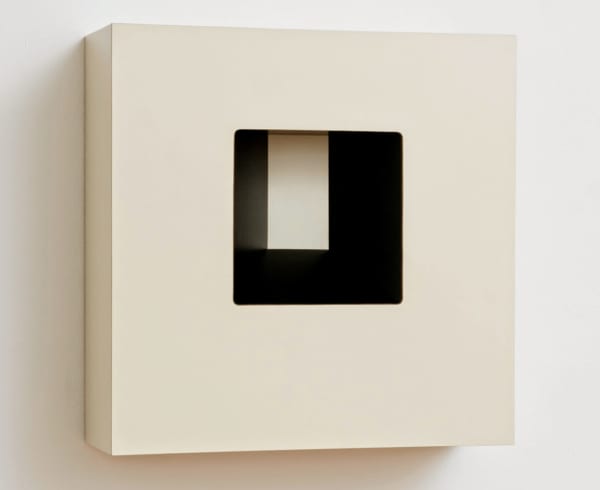

Richard ArtschwagerQuotation Marks, 1980Formica and painted wood, in two partseach: 15 1/2 x 11 x 2 in (39.4 x 27.9 x 5.1 cm)Edition of 25 (AP), published by Multiples, Inc., New York

Richard ArtschwagerQuotation Marks, 1980Formica and painted wood, in two partseach: 15 1/2 x 11 x 2 in (39.4 x 27.9 x 5.1 cm)Edition of 25 (AP), published by Multiples, Inc., New York -

-

-

Richard ArtschwagerSee by Looking / Hear by Listening, 1992melamine laminate, wood, velvet, chrome plated brass and etched glassoverall (open): 14 1/8 x 24 1/16 x 15 in (35.9 x 61.1 x 38.1 cm)Edition of 7

Richard ArtschwagerSee by Looking / Hear by Listening, 1992melamine laminate, wood, velvet, chrome plated brass and etched glassoverall (open): 14 1/8 x 24 1/16 x 15 in (35.9 x 61.1 x 38.1 cm)Edition of 7 -

-

Richard ArtschwagerDoor, 1987Formica and wood with metal hardwareoverall (closed): 17 x 25 x 3 7/8 in (43.2 x 63.5 x 9.8 cm)Edition of 25 (#12/25), published by Brooke Alexander Editions, New York

Richard ArtschwagerDoor, 1987Formica and wood with metal hardwareoverall (closed): 17 x 25 x 3 7/8 in (43.2 x 63.5 x 9.8 cm)Edition of 25 (#12/25), published by Brooke Alexander Editions, New York -

-

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood and hardware9 x 18 1/2 x 6 in (22.9 x 47 x 15.2 cm)Edition of 40 (#9/40)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood and hardware9 x 18 1/2 x 6 in (22.9 x 47 x 15.2 cm)Edition of 40 (#9/40) -

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood and metal hardware21 1/2 x 7 x 7 in (54.6 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm)Edition of 40 (#33/40)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood and metal hardware21 1/2 x 7 x 7 in (54.6 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm)Edition of 40 (#33/40) -

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood and metal hardware10 x 10 x 10 in (25.4 x 25.4 x 25.4 cm)Edition of 40 (#1/40)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood and metal hardware10 x 10 x 10 in (25.4 x 25.4 x 25.4 cm)Edition of 40 (#1/40) -

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood with metal hardware5 x 16 x 12 1/2 in (12.7 x 40.6 x 31.8 cm)Edition of 40 (#26/40)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (1000 cubic inches), 1996wood with metal hardware5 x 16 x 12 1/2 in (12.7 x 40.6 x 31.8 cm)Edition of 40 (#26/40) -

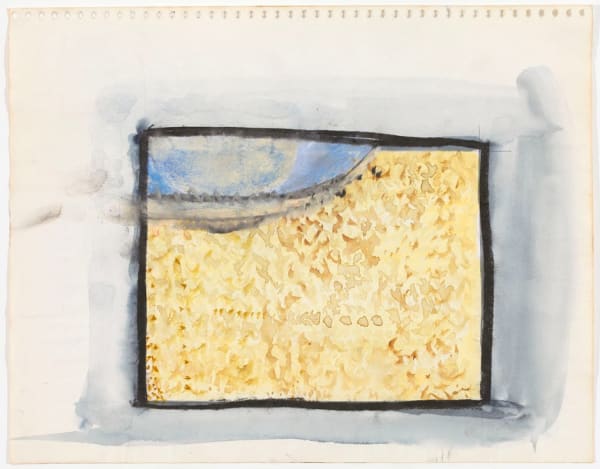

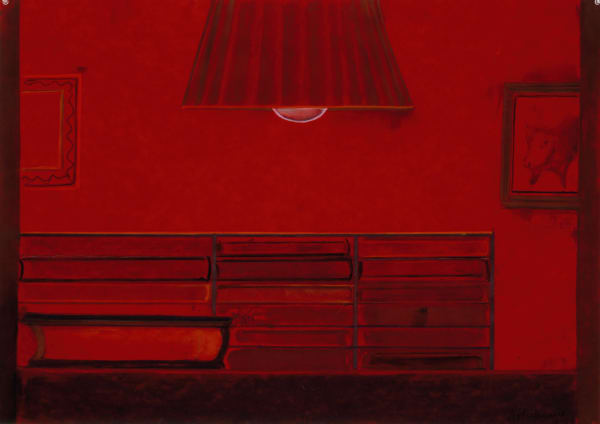

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled, c. 1958/59watercolor and graphite on paper10 7/8 x 13 7/8 in (27.6 x 35.2 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled, c. 1958/59watercolor and graphite on paper10 7/8 x 13 7/8 in (27.6 x 35.2 cm) -

-

-

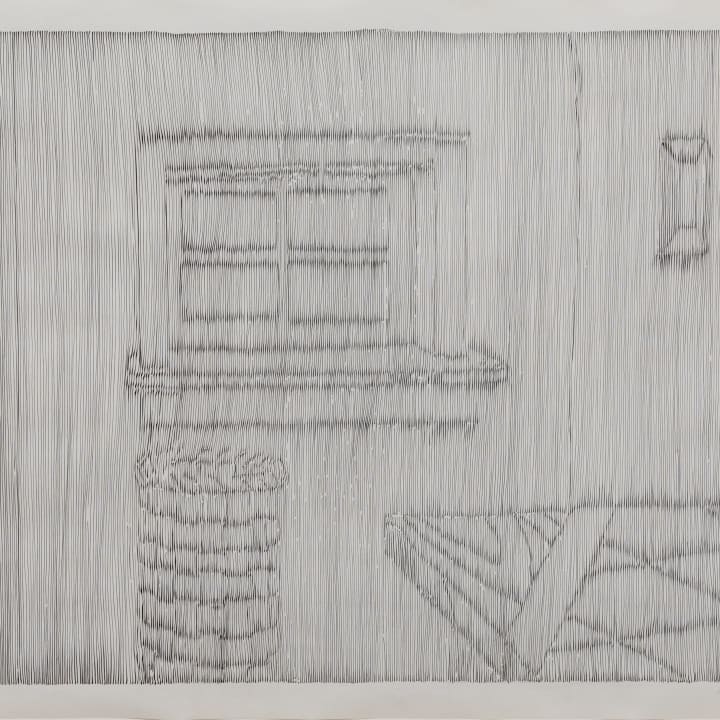

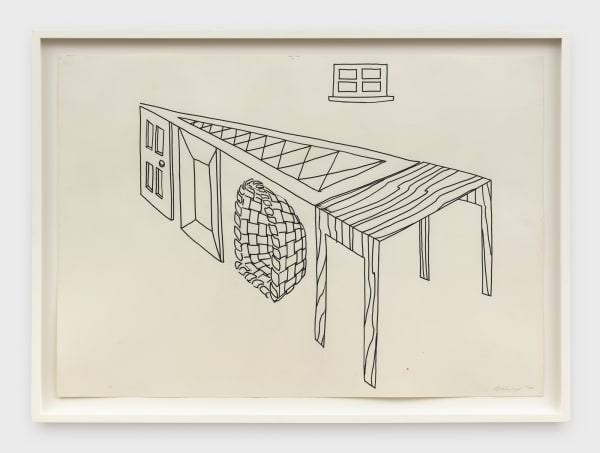

Richard ArtschwagerDoor, Window, Table, Basket, Mirror, Rug, 1974ink on paper19 1/2 x 28 in (49.5 x 71.1 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerDoor, Window, Table, Basket, Mirror, Rug, 1974ink on paper19 1/2 x 28 in (49.5 x 71.1 cm)

framed: 23 x 31 1/2 x 1 1/2 in (58.4 x 80 x 3.8 cm) -

-

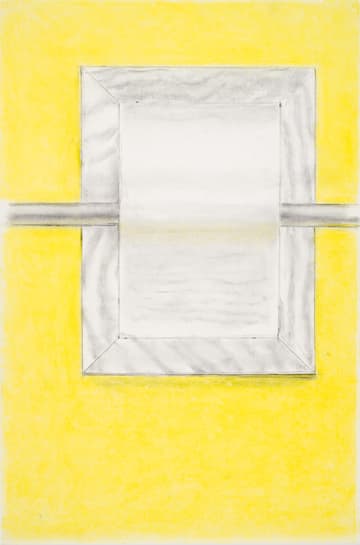

![Richard Artschwager Untitled [Interior], 1977 pencil on paper 33 x 23 in (83.8 x 58.4 cm)](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Richard ArtschwagerUntitled [Interior], 1977pencil on paper33 x 23 in (83.8 x 58.4 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled [Interior], 1977pencil on paper33 x 23 in (83.8 x 58.4 cm) -

-

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (Weave), 1978charcoal on paper18 x 22 in (45.7 x 55.9 cm)

Richard ArtschwagerUntitled (Weave), 1978charcoal on paper18 x 22 in (45.7 x 55.9 cm)

framed: 28 x 32 x 1 1/4 in (71.1 x 81.3 x 3.2 cm) -

-

Robert MapplethorpeRichard Artschwager, 1986silver gelatin silver printimage: 19 1/8 x 19 1/8 in (48.6 x 48.6 cm)

Robert MapplethorpeRichard Artschwager, 1986silver gelatin silver printimage: 19 1/8 x 19 1/8 in (48.6 x 48.6 cm)

sheet: 24 x 20 in (61 x 50.8 cm)Edition of 10 plus 2 AP's

-

-

PRESS

-

The Maverick Art of Richard Artschwager

John Yau · Hyperallergic January 10, 2024Richard Artschwager (1923–2013) was 42 when he had his first solo show. The exhibition, which was at Leo Castelli gallery, included the Formica sculpture “Table with Pink Tablecloth” (1964), now... -

Richard Artschwager: Boxed In | Celebrating the Artist’s Centennial

Alfred Mac Adam · Brooklyn Rail January 1, 2024“I am not what I am.” Ominous words spoken by Iago in Othello, but in the case of Richard Artschwager a definition of aesthetic principle. We can change the meaning... -

Richard Artschwager

Jan Avgikos · Artforum January 1, 2024Richard Artschwager (1923–2013) was a maestro of shape-shifting sculptures, tricky dematerializations, and other feats of visual and semiotic mischief. He possessed an enduring fascination with the unremarkable and defamiliarized the...

-

-

Artist

RICHARD ARTSCHWAGER: BOXED IN: Celebrating the Artist's Centennial,

December 15, 2023 - January 20, 2024MAILING LIST SIGN-UP

By completing this form, you confirm that you would like to subscribe to DAVID NOLAN’s mailing list and receive information about exhibitions and upcoming events. Your email address will be used exclusively for the mailing list service.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.

![Richard Artschwager Untitled [Interior], 1977 pencil on paper 33 x 23 in (83.8 x 58.4 cm)](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/davidnolangallery/images/view/298ff1f0ec372cb212fb7de230882c6ej/davidnolangallery-richard-artschwager-untitled-interior-1977.jpg)