STEVE DIBENEDETTO: Uncertainty Takes a Holiday

-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is pleased to present Steve DiBenedetto: Uncertainty Takes a Holiday, the artist’s fourth solo show with the gallery, on view from October 26 through December 9, 2023. The exhibition will include both paintings and works on paper, all created within the last two years.

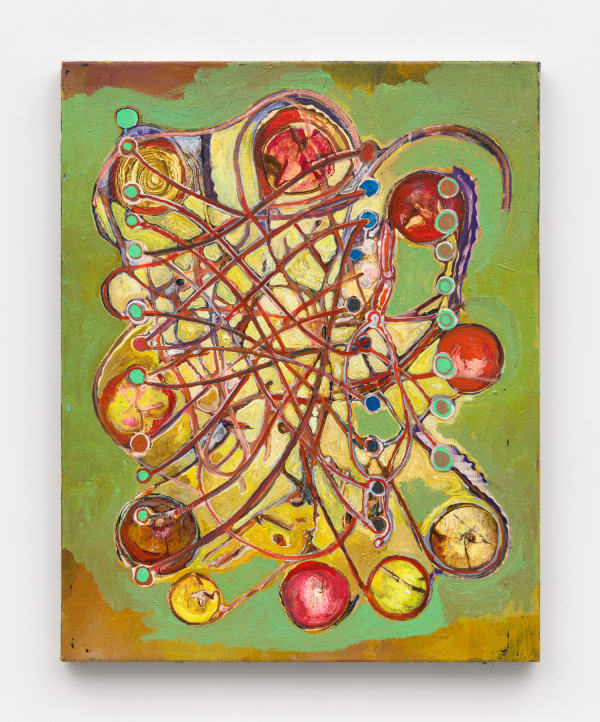

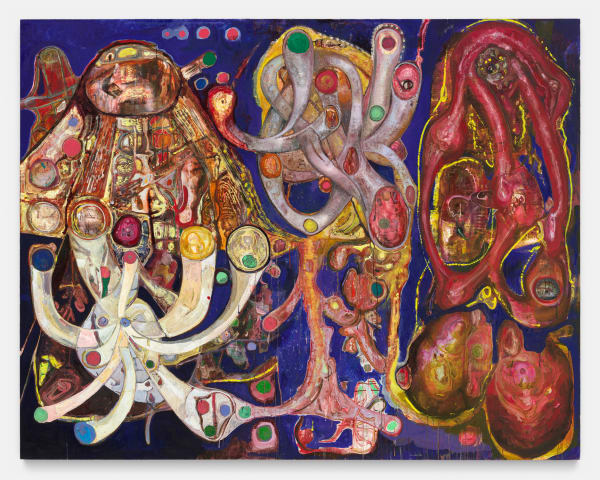

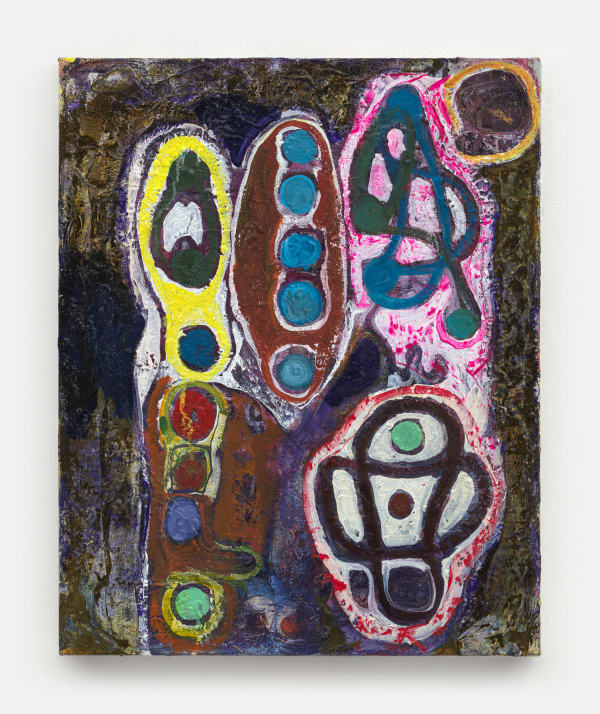

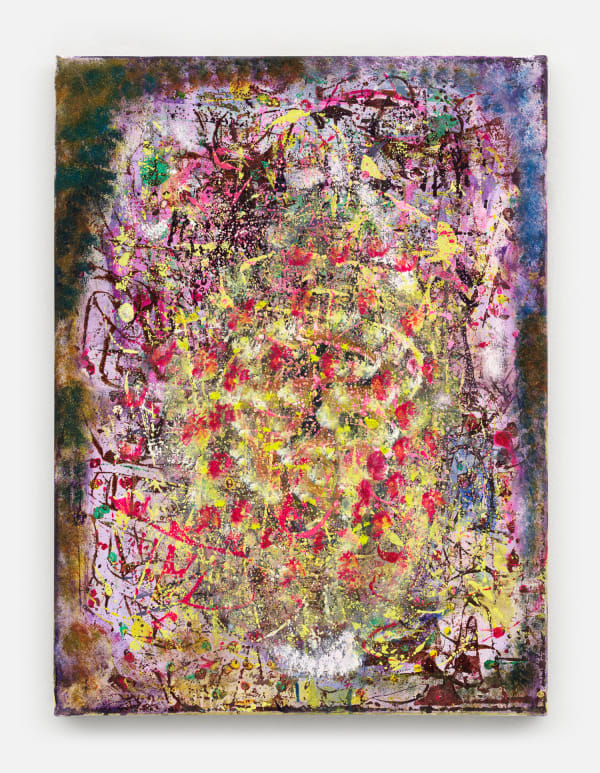

Possessed by a desire to “maximize” a painting, DiBenedetto continues to find new ways to exploit the possibilities of oil paint through crusty, built-up surfaces and bright, jewel-toned shapes that gleam in the midst of gritty, impastoed muck. Though he can apply paint so thickly it might qualify as bas-relief, the forms themselves are flattened into the background in a way that often feels like massive amounts of time and space have been compressed into a single plane. As always, DiBenedetto is working out his ideas on the canvas, adding and subtracting elements in an iterative process such that even when a work is finished, the agitation of its creation remains visible on the surface.

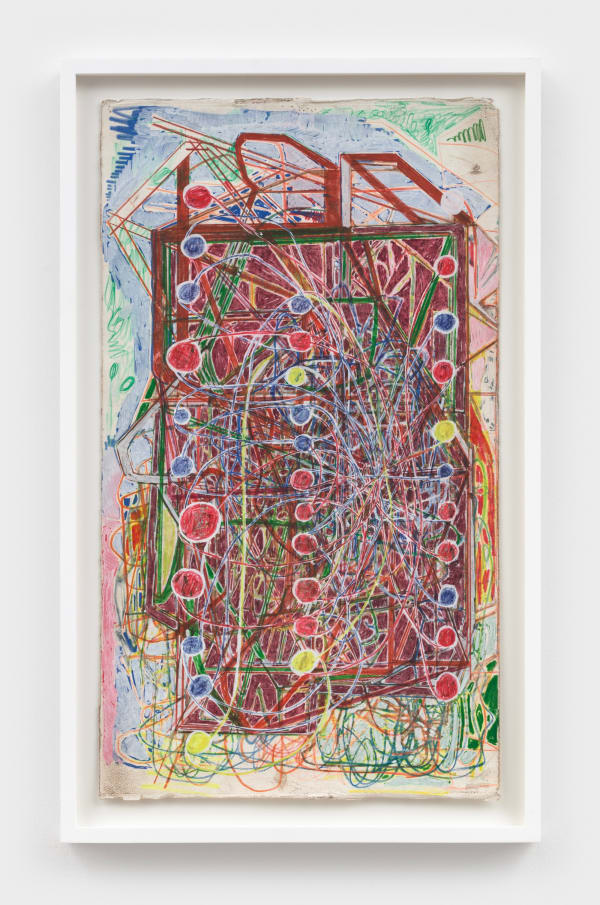

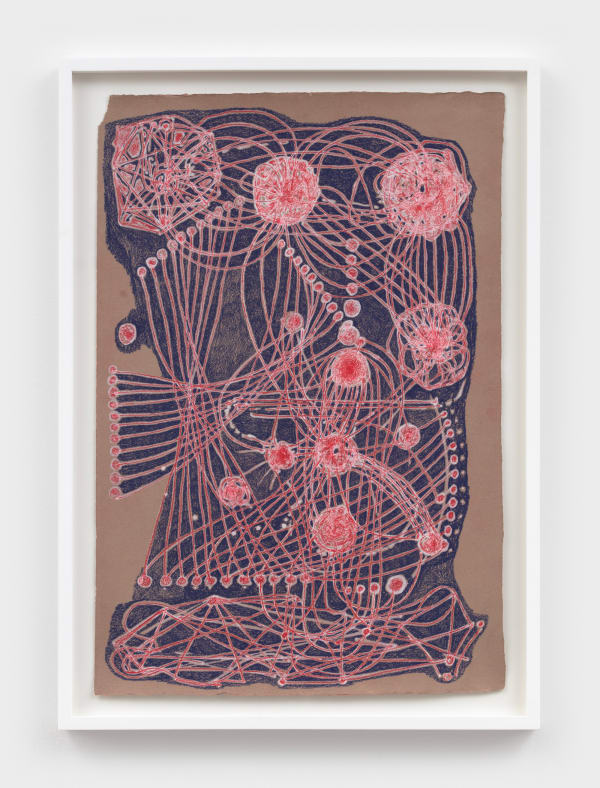

Throughout his career, DiBenedetto’s work has reflected his intellectual interests, from his early investigations into the transmission and erosion of information and the vibrations of technology, to his well-known explorations of states of altered consciousness through the iconography of the octopus, the helicopter and the ferris wheel. Most recently, DiBenedetto’s attention has been fixated on theoretical physics: quantum mechanics, the Big Bang, string theory and its idea that our universe exists in eleven dimensions. Suddenly, the 11-tentacled structures in his paintings make sense, the circular whorls at their termini now understood as portals into other realms.

In the painting titled Uncertainty Takes a Holiday (2022-23), a dark form stretches its tentacles, some of which appear to contain eyes at their tips, others that end in circles containing their own little miniature abstractions. DiBenedetto shapes the arms into rounded, embodied forms that reach out from some nebulous, murky space, seeming to glow with the yellow and white light emanating from somewhere behind it — a holy radiance for the scientific age. By contrast, Higgs Hippy HellHole (2022) feels relatively flattened: portals fashioned from one or two saturated hue, tentacles crossing each other in the same plane within a golden field that doesn’t glow so much as it stuns with its assertiveness.

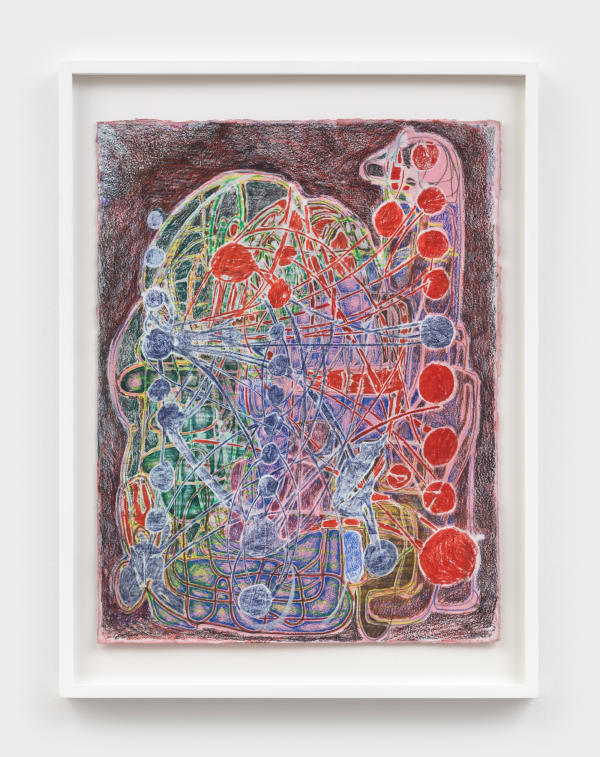

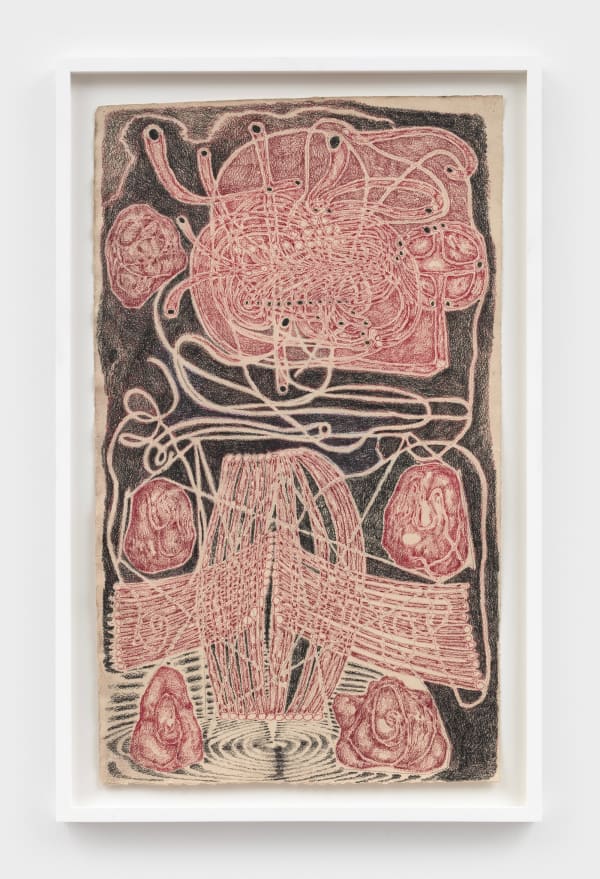

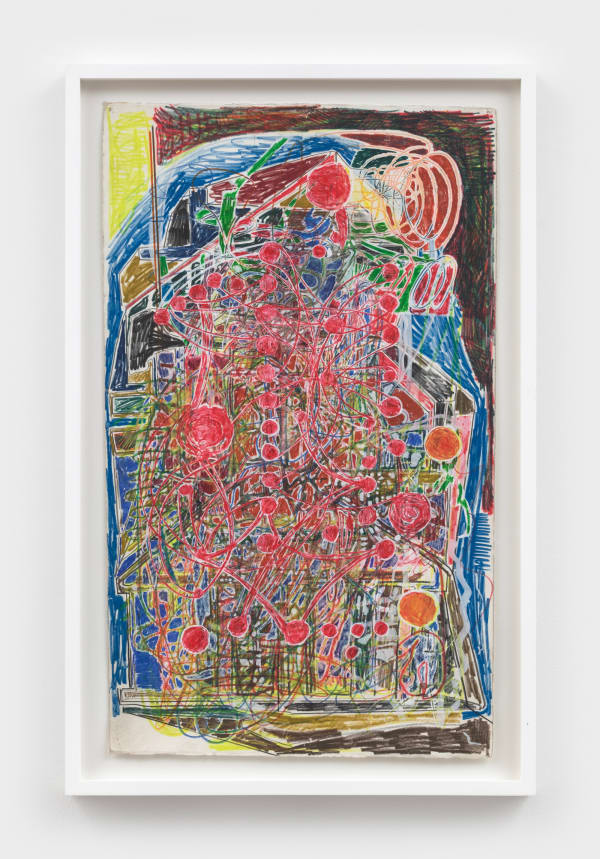

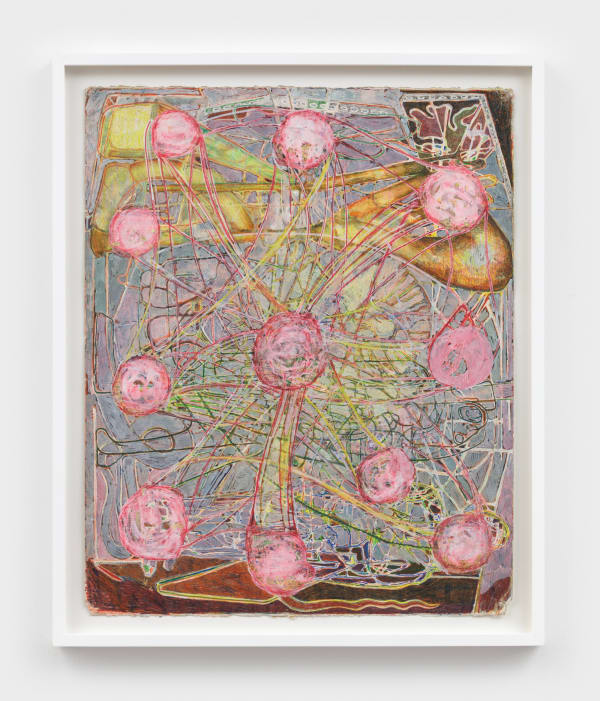

DiBenedetto executes his finely detailed drawings in colored pencil and a particular type of white ink marker he favors for the way it allows the pencil pigment to “ooze” through, creating a grayish, ghostly shade. Part of what makes them particularly dazzling is the way in which DiBenedetto fuses his theoretical diagrams with contemporary digital technologies, delineating cosmic pathways that resemble computer circuitry or neural networks at a moment when human and artificial knowledge feel uncomfortably indistinguishable. In this sense, the artist has never really abandoned his early enchantments with technological dystopias or the centrifugal motion of the helicopter, for what is the Big Bang if not centrifugal force writ galactically large?

-

Installation Views

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Steve DiBenedettoPortrait of God by A.I., 2023oil on linen20 x 18 in (50.8 x 45.7 cm)

Steve DiBenedettoPortrait of God by A.I., 2023oil on linen20 x 18 in (50.8 x 45.7 cm) -

-

-

-

-

Steve DiBenedettoSynapse Fish, 2022colored pencil on paper22 1/2 x 12 3/4 in (57.1 x 32.4 cm)

Steve DiBenedettoSynapse Fish, 2022colored pencil on paper22 1/2 x 12 3/4 in (57.1 x 32.4 cm)

framed: 25 1/4 x 15 1/2 in (64.1 x 39.4 cm) -

-

-

Steve DiBenedettoWooden Atomic Clock, 2022colored pencil on paper22 x 17 3/4 in (55.9 x 45.1 cm)

Steve DiBenedettoWooden Atomic Clock, 2022colored pencil on paper22 x 17 3/4 in (55.9 x 45.1 cm)

framed: 24 3/4 x 20 1/2 in (62.9 x 52.1 cm)

-

-

PRESS

-

Steve DiBenedetto’s Art Embraces Incoherence

John Yau · Hyperallergic November 28, 2023Two distinct but related artists seem to inhabit Steve DiBenedetto’s consciousness: the one who paints fibrous forms in oil and pigment and the one who draws shapes in colored pencil... -

Steve DiBenedetto: Uncertainty Takes a Holiday

Featuring DiBenedetto and Dan Nadel, with James Sherry · Brooklyn Rail November 6, 2023Artist Steve DiBenedetto joins Rail contributor Dan Nadel for a conversation. We conclude with a poetry reading by James Sherry.

-

-

Artist