“Every material has its own voice,” Dorothea Rockburne tells me. It’s a sunny afternoon in August, and we’re sitting in the SoHo loft where the artist has lived and worked for the past 50 years. I had asked Rockburne to explain what the phrase truth in materials meant to her, as I’d heard she was a big fan of the Bauhaus concept. “If you have a sheet of paper, it will fold, it will tear, it will reassemble,” the spirited 95-year-old explains. But you can’t force it to do something against its nature—a blessing disguised as a limitation.

It makes sense that someone with such reverence for materials has experimented with the wide variety Rockburne has: paper, vellum, grease, graphite, rope, linen, tar, chipboard, or any number of things she might find at the hardware store. Each has its own language, uniquely suited to exploring heady topics like set theory, topology, and astronomy. Her interest in mathematics, picked up during her years at the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina, was not exactly de rigueur in the 1960s, when she was getting a foothold in the New York art world. And beyond her outlier aesthetics, Rockburne was a single mother in a male-dominated scene. But she persisted, and the paintings, sculptures, and installations she has produced over the last seven decades have cemented her status as a leading, if undersung, figure of contemporary American art.

What a boon for Londoners, then, that her work should come to their city. Last week Bernheim gallery’s London outpost opened “The Light Shines in Darkness and the Darkness Has Not Understood It,” a four-decade survey of more than two dozen of Rockburne’s works curated by Lola Kramer. The show traces the ever-inventive Rockburne’s oeuvre from her early works with wrinkle-finish paint to her elegant folded-linen Egyptian Paintings to her vibrant later pieces inspired by cosmology.

The show is Rockburne’s first European survey in decades; much of the art on display has never been shown outside the US at all, partially because Rockburne’s work does not make for easy installation. “It’s all based on mathematical theories, formulas, or philosophy, so for her every line has to be exact,” Kramer says.

Rockburne’s Domain of the Variable, a seminal multipart work originally from 1972 that graced the cover of Artforum’s March issue that year, is one piece that required particular care in its re-creation. The Bernheim installation includes a line cut into the wall that stretches through the whole first floor of the gallery’s town house—a nod to Rockburne’s spatial thinking. Kramer first saw Domain as part of Rockburne’s Dia: Beacon show that ran from 2018 to 2022. For that iteration, some materials had to be substituted because the 1970s originals were either no longer available (like cup grease) or had been discarded decades prior during de-installation. To the artist, both the 2018 and 2024 re-creations are different manifestations of the same mathematical theory. “It’s almost like a time-traveling artwork,” Kramer says.

Rockburne, born in Montreal in 1932, studied painting and philosophy in Canada before moving to the US to attend Black Mountain College at age 18. “When I was in Montreal, I knew that if I went to McGill I would go in as Dorothea and come out as a dietitian. I wasn’t looking for a job. I was looking for an education,” she tells me.

At Black Mountain, she got one. “You were only allowed to take three classes, but you were allowed to sit in on anything you wanted. I sat in on everything,” she says. She studied painting with Jack Tworkov and Franz Kline; dance with Merce Cunningham; music with John Cage. She developed deep friendships with fellow students like Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly.

But the most influential of all was the German mathematician Max Dehn, whose geometry class Rockburne wandered into one day. “I was always interested in geometry, but I didn’t know where geometry could take me, exactly,” Rockburne recalls. “I just hung in the doorway, and Max said, ‘Come on in and sit down.’ He had a way of drawing that was beautiful.” She watched him do complex equations, and even without full technical comprehension, she was hooked. Dehn went on to introduce Rockburne to mathematical concepts found in nature and art, like the golden ratio. He also gave her books and recommended philosophers.

Rockburne got married and gave birth to a daughter at Black Mountain before moving to New York City in 1954. Her marriage ended not long after. She was still young, in her early 20s. To support herself and her child, she held various jobs—including as Rauschenberg’s studio manager—while continuing to make her own art at night. Sleep was scarce, but she made it work. “It was either that or not be an artist, and I was always an artist.”

I asked how her experience was working for Rauschenberg. “Mixed,” she says. “Bob was a force. We loved each other, being around him was a great pleasure.” But it was also the time of the macho male artist. Rauschenberg and his crew didn’t understand her interest in math, nor the obligations of parenthood, much less single motherhood. “When I first wanted a credit card, I was working for Bob and he had to sign for me.”

Movement has always been important to Rockburne. She started taking ballet at age four. In New York she joined the Judson Dance Theater, the revolutionary group that was known for recruiting non-trained dancers. Rockburne calls it “a remarkably intelligent experience” for how it embraced the unpredictable. Even after she left Judson to focus more on her art, she kept up the physicality, always working while standing up or crouched over her work. “I never drew from my wrist. And when I taught drawing, I wouldn’t let anyone sit down. You have to work from your whole body,” she says.

Before the late 1960s, Rockburne didn’t show her work much, besides to close friends. But by 1970 she was in a bunch of group shows, including at the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, and Paula Cooper Gallery. Her first solo show came in 1971, at the short-lived but influential Bykert Gallery, where Domain of the Variable was first staged. More shows and museum acquisitions followed. The critical response to her work was positive, especially in recognition of her unique vision. A 1977 article in Vogue by the art critic Barbara Rose praised “the cool lucid geometry of Dorothea Rockburne.”

“One admires artists like Rockburne and [Nancy] Graves,” Rose wrote, “who have enough conviction to go through the long and painful process of trying to make original art that will stand up to criticism and judgment in the future as well as to attract attention in the present.”

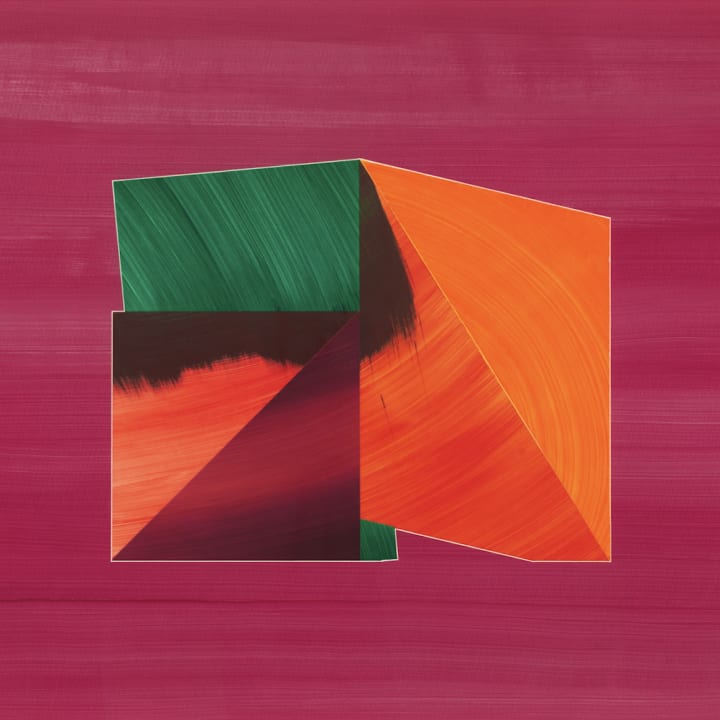

In the 1980s, Rockburne started making vivid geometric works with oil paint—like the fiery Inner Voice (1983) and lush Interior Perspective, Discordant Harmony (1985, pictured above), both on view at Bernheim in London. These are some of the best examples of Rockburne’s signature blend of fine-art techniques, acquired during her classical training at Montreal’s Écoles des Beaux-Arts, with the more avant-garde approach of Black Mountain College.

Rockburne similarly blended her interest in mathematical and scientific theories with her more ineffable influences: ancient Greek mythology, Egyptian art, the Renaissance, and the work of philosophers like Pascal. “She’s very interested in the sublime. The idea of mathematics is the means of getting there,” says Kramer.

Despite her success in gallery and group shows, and with commissions for the lobby of Philip Johnson’s 550 Madison skyscraper and the US Embassy in Jamaica, Rockburne did not receive a career retrospective until her Parrish Art Museum show 2011. A monographic show at MoMA followed in 2013, and then the Dia survey a few years later. Finally, it seems wider recognition has arrived.

Sitting in Rockburne’s SoHo loft, I wonder how much she thinks about all this history, and her legacy. “I don’t really have a recognition of time the way normal people do,” she says. It’s always been like that for her—she’s more focused on the work. “When I walk into the studio, I transform. Something happens, and I’m different.”

It’s a transformation one can pick up on in her art. Yes, there’s a high level of both conceptual and mathematical thinking she pours into it. But the viewer doesn’t need to know a thing about set theory to find her organization of lines and angles beautiful. The repetition, the layering, the use of light and shadow—it all adds up to much more than the computational parts.

Rockburne points at a math magazine on her coffee table, encouraging me to pick it up. “It doesn’t matter if you don’t understand it,” she says, correctly clocking that my math education topped out in high school. “You could just look at the pictures and you’ll get something out of it.”

“The Light Shines in the Darkness and the Darkness Has Not Understood It” is on view at Bernheim gallery in London through January 25, 2025.