The last time we had a chance to be disquieted by Erwin Pfrang’s phantasmagoria was back in 2002. We who remember 2002 have missed him; younger people now have the enviable chance to see his work for the first time. Pfrang was born in 1951, in Munich, the capital city of German Expressionism and home of the 1911 Blue Rider group. His birthplace and his relationship to Expressionism are a problem.

The problem arises from the deterministic view of artists and art, which declares artists’ race, class, and gender to be the determining factors in the meaning of their work. No critic of Pfrang fails to mention his debt to Expressionism, from James Ensor and Edvard Munch down to Max Beckmann and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. And rightly so, but we should not use that association to write off Pfrang as “just another German Expressionist.” Sometimes a prodigy like Pfrang takes control of an extant style and produces something new. And this is the point: Erwin Pfrang works in an expressionist idiom, but he makes it his own language.

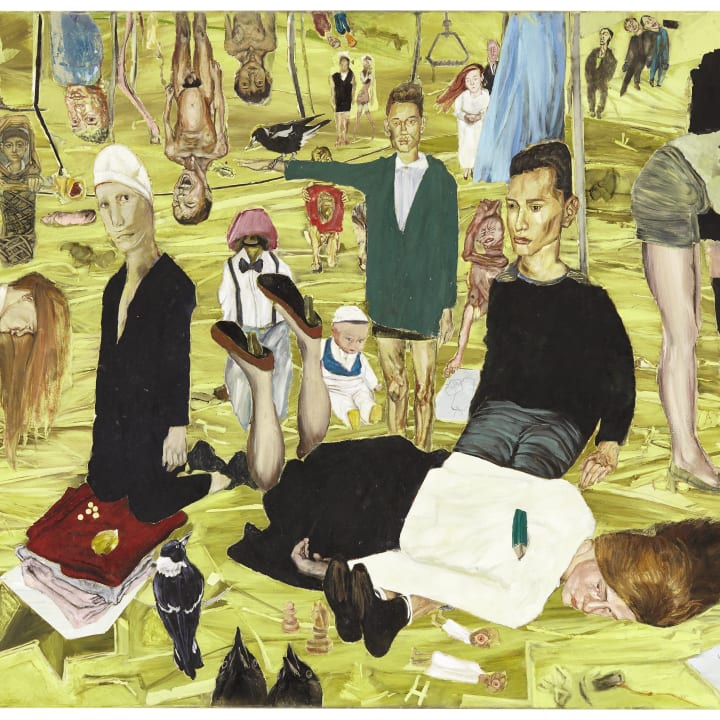

The basic traits of expressionist art—distortion, exaggeration, unnatural color—all appear in Pfrang’s work, but something else makes his work unique. Pfrang produced the thirty-four drawings and paintings in this show between 2007 and 2024, but they do not constitute a retrospective. This is because of Pfrang’s signature style: we don’t expect radical changes in his work. What we do want—and get—is a process of perpetual exploration of artistic possibilities. Any changes, doubtless important to the artist himself, are insignificant to viewers, especially those unfamiliar with his work.

Where tradition and pictorial perspective get smashed to bits is the astounding 2022 oil on canvas Erlkönigs Töchter [Erlking’s Daughters]. The point of departure is a 1782 ballad by Goethe in which a father carries his son on horseback in a wild escape while the son feels he is being pursued by the Fairy King, who speaks to him:

Do you, fine boy, want to go with me?

My daughters shall wait on you finely;

My daughters lead the nightly dance,

And rock and dance and sing you to sleep.

These daughters are not comforting angels. Pfrang includes two of the daughters, one a sexy siren with a horribly mutilated sex, the other (on the right) an androgyne guffawing on the shoulders of a strongman wearing a gas mask. In the center, the Fairy King wears half a military uniform that Pfrang outlines by incising into the paint and adorns with a bright red Iron Cross on his chest. All around these figures, in fluctuating perspective, are dozens of figures—adults, children—alive or soon-to-be dead. If hell is chaos, where two and two do not make four, where all perspectives jumble, then Pfrang has depicted hell. Unbelievable, impossible to forget.